Despite the increase in missile-defense production among Europe and its allies, they still cannot keep up with Russia’s missile output. Although Russia produces roughly one and a half to two times more ballistic and cruise missiles than Europe’s interceptor missiles, it also surpasses Europe by a wide margin in long-range UAV production. Moreover, dependence on expensive next-generation interceptor missiles makes Europe’s missile-defense strategy inherently cost-inefficient and unsustainable in the long run.[1] In European military history, as seen in the Napoleonic Wars and World War I, the firepower of the artillery branch has been the decisive weapons system in nearly all major land battles. In World War II, in land warfare and artillery support, tanks and missiles—along with close air support from fighter aircraft—became the determining factors of battlefield superiority. Instead of losing relevance, the future of warfare will likely be shaped by a rising demand for both offensive and defensive fires.[2] Experiences from the 1991 Gulf War and the Kosovo War brought several strategies to the forefront and clearly demonstrated the superiority of airpower. Although strategic airpower alone cannot win a war, as clearly shown in the Gulf War, it greatly facilitated the ground forces’ complete destruction of the Iraqi Army.[3]

The Game-Changing Weapon in the Nature of the Future Battlefield: Hypersonic Missiles

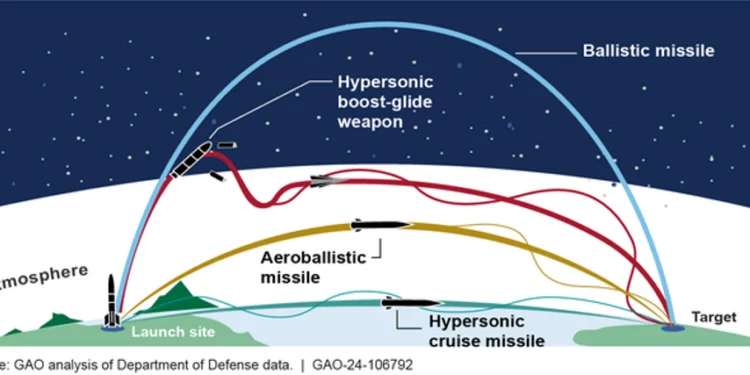

Direct threats to the mainland were initially limited to long-range aviation, but were later expanded to include ICBMs, submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and cruise missiles. Today’s new missile era is defined by the increase in global supply and demand for strike capabilities of various ranges and the defensive systems designed to counter them.[4] For Türkiye, the greatest foresight in missile technologies—required by the shifting strategic and geopolitical environment—is to demonstrate determination in rapidly adapting to change and taking corresponding countermeasures; this is essential for sufficient regional peace and deterrence. Over the next twenty years, military conflicts will likely continue to be driven by the same factors that have historically triggered wars—from resource protection, economic inequalities, and ideological differences to the pursuit of power and influence—yet the ways in which war is conducted will change as new technologies, applications, and doctrines emerge and as additional actors gain access to these capabilities. However, the artillery branch and missiles will fundamentally remain the same in their purpose of waging war, guiding current modernization programs.

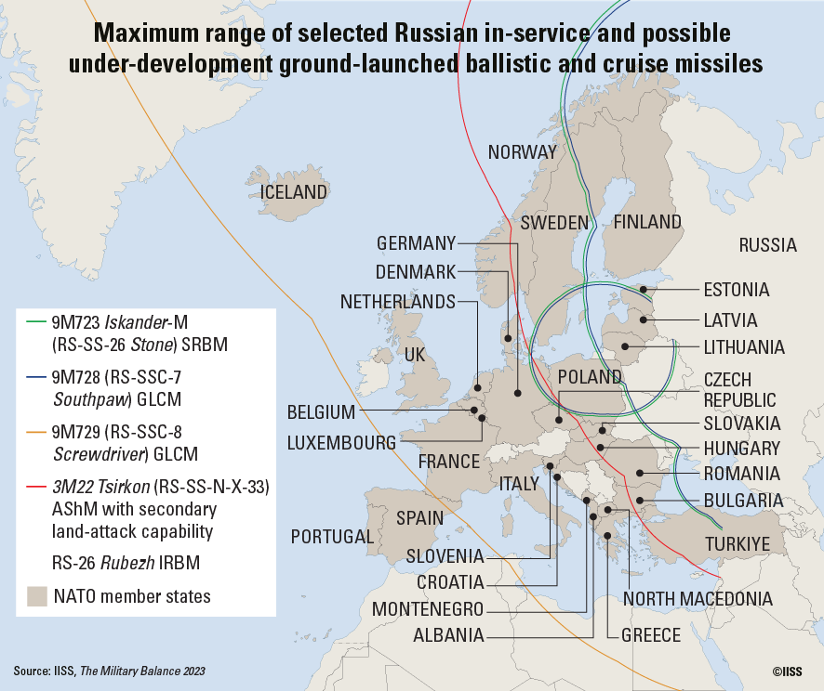

Ranges of Russia’s Ballistic and Cruise Missile Classes

Artificial intelligence, hypersonic weapons, and other disruptive technologies such as electronic warfare are also extremely important. Therefore, the risks are enormous—far greater than at any time since the Cold War or even World War II—and the consequences are extraordinary. “Business as usual” is not possible.[5]

Ukraine’s new FP-5 “Flamingo” cruise missile, with a range of 3,800 km, represents an interesting development in Ukraine’s strike capabilities as the war with Russia continues. Ukraine’s preference for cruise missiles over ballistic missiles reflects a pragmatic assessment of cost-effectiveness ratios. The United States, Russia, and China are responding by shifting away from ballistic missiles in favor of Long-Range Hypersonic Weapons (LRHW) and Hypersonic Glide Vehicles (HGV). However, such systems—costing 41 million dollars per missile—are beyond the budgets of European countries.

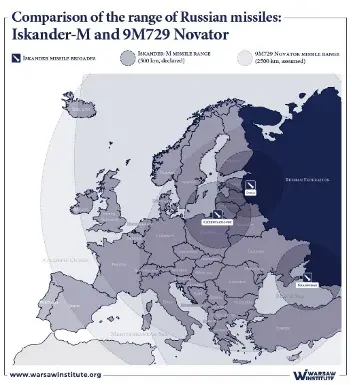

In Europe, the priority in acquiring deep-strike capability remains the restoration of a missing capacity in significant quantities and within a short timeframe, rather than procuring a small number of extremely high-end missiles. Russia is increasingly relying on Iskander-M missiles to strike Ukrainian positions and is importing KN-23 missiles from North Korea.

The truth is that Europe already possesses a strong industrial infrastructure in cruise-missile technology. The Naval Cruise Missile (MdCN/NCM), deployed from French frigates and submarines, has proven itself under combat conditions in Syria.

French MBDA Deep-Strike Cruise Missile and Its Naval Variant

MBDA has proposed the Land Cruise Missile (LCM), a ground-launched system with a range of more than 1,000 kilometers, terrain-following flight capability, and high endurance, building on this foundation and branding it as a “unique European sovereign solution.” The Franco-British-Italian joint project Stratus—also known as the Future Cruise/Anti-Ship Weapon (FC/ASW)—is progressing toward the development phase. Designed in two complementary variants, one stealthy and subsonic, the other supersonic and maneuverable, the program reflects a deliberate choice to complicate enemy air defenses and ensure penetration capability by combining range, precision, and stealth. According to MBDA, Stratus aims to enter service before 2030 and will replace the current SCALP/Storm Shadow inventories.[6]

The combination of improved sensors, automation, and artificial intelligence (AI) with hypersonics and other advanced technologies will produce weapons that are more accurate, more connected, faster, longer-ranged, and more destructive; while these may initially be available primarily to the most advanced militaries, some will eventually become accessible to smaller states and non-state actors. The gradual proliferation and diffusion of these systems will make more assets vulnerable, increase escalation risks, and potentially render conflicts more lethal—though not necessarily more decisive.[7]

The skies of the Middle East and Eastern Europe have reflected the emergence of a new operational environment in modern warfare. From drone swarms over Ukrainian front lines to Iran’s precision ballistic-missile strikes against Israel, and to Houthi operations in the Red Sea and beyond, recent conflicts are reshaping strategic thinking around air and missile defense. For the Arab Gulf states, these developments serve as indicators of future risks.

Range of U.S. ATACMS Missiles

As both state and non-state actors increasingly exploit more sophisticated offensive capabilities, the Arab Gulf states must reassess their preparedness against these emerging threats.[8] Indeed, the use of anti-tank weapons in Ukraine was initially perceived as a sign of the demise of armored vehicles. Similarly, in the conflicts that have persisted for five years across the Black Sea and Ukrainian territory, the arrival of mass unmanned platforms on land, at sea, and in the air has been seen as an omen of the decline of advanced tactical aircraft and naval vessels. The emergence of numerous non-kinetic and electronic-warfare tools has led to predictions that, even if traditional kinetic fires do not entirely become relics of the past, they will at least become less significant than before.[9]

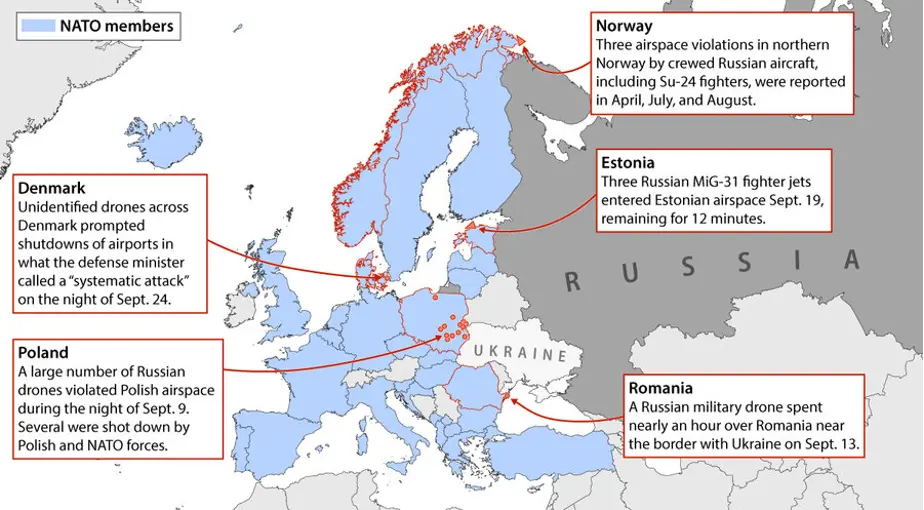

We have seen drone warfare become widespread on the Ukrainian battlefields and in the Israel-Hamas war. The U.S. homeland has also been exposed to drone attacks. This year, the Congressional Military and Foreign Relations Subcommittee identified more than 350 drone attacks across 100 different military facilities in 2024. Most recently, in September, NATO countries Poland and Romania also reported drone incursions, with 19 Russian drones entering Polish airspace. This prompted Warsaw to invoke NATO’s Article 4, requiring urgent consultations.

The increasing use of low-cost drones is rapidly becoming a preferred tool in hybrid warfare. Drones are not only used for low-cost kinetic strikes but are also effective in surveillance, intelligence gathering, disrupting civilian infrastructure, and creating fear and political tension among the public. In the future, low-cost hybrid drone warfare—bolstered by advances in artificial intelligence—poses a real and immediate challenge to establishing reliable, scalable air defense.

Russian UAV Attacks

This situation has triggered efforts to reassess the capabilities of existing air-defense systems and to review modernization plans in order to counter drones and other threats effectively and efficiently.[10] On the night of 9 July 2025, Russia launched the largest combined unmanned aerial vehicle and missile attack of the Russia-Ukraine war, saturating Ukraine’s defenses with 728 kamikaze drones and 13 missiles, most of them targeting Kyiv. The scale was staggering. And it was not an isolated event. In the following days, two more salvos struck Ukraine—416 weapons in one wave and 625 in another—each exceeding the daily averages seen in previous months.

These attacks were much more than a simple increase in Russian activity. They signaled a deeper and deliberate shift in operational tempo and sent a message to Ukraine and its supporters: Russia is prepared to escalate, overpower, and exhaust Ukraine. Mass salvo attacks are part of Russia’s evolving coercive-punishment campaign. What was once exceptional has become routine. Large-scale salvo strikes now constitute roughly 10% of all Russian air operations. Russia’s combined use of ballistic and cruise missiles alongside kamikaze UAVs has demonstrated how such systems can mutually reinforce each other against an adversary’s air-defense architecture.[11]

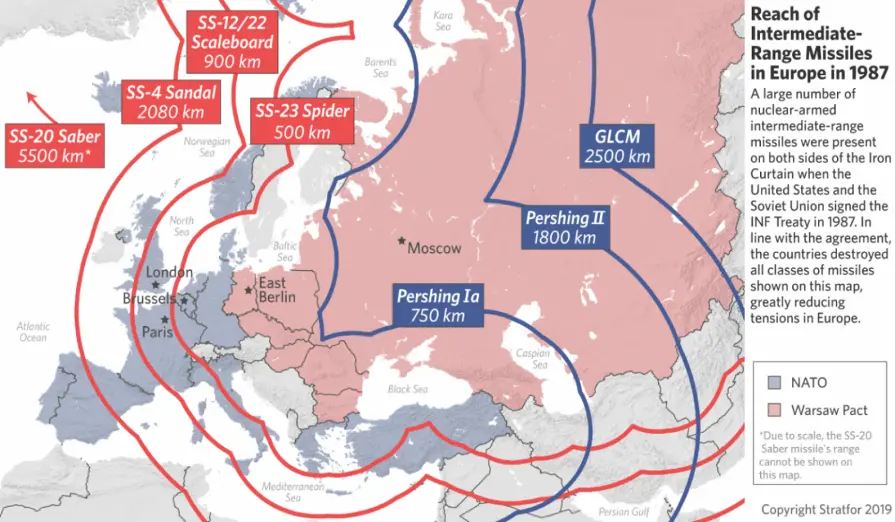

1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty

President Vladimir Putin told European powers that if they entered a war with Russia, Moscow would be ready to fight, and their defeat would be so decisive that no one would remain to negotiate a peace agreement. Putin asserted that Russia does not want a war with Europe. “If Europe suddenly wants to start a war with us and does start it,” he said, it would end so quickly for Europe that Russia would have no one left to negotiate with. Putin used the Russian word meaning “war.”[12]

Following Putin’s statements threatening that Russia is prepared for war with Europe, it was reported that no progress has been made toward a peace agreement between Russia and the United States regarding Ukraine. Putin accused European powers of sabotaging peace in Ukraine and said that “European demands” regarding ending the war are “unacceptable to Russia.” Putin stated, “Europe is preventing the U.S. administration from achieving peace on Ukraine,” adding: “Russia is not considering fighting Europe, but if Europe starts, we are ready immediately.” Putin did not specify which European demands he found unacceptable. Referring to the European powers, Putin stated, “They are on the side of the war.”[13]

Russian President Vladimir Putin, following recent tanker attacks in the Black Sea, has threatened to cut off Ukraine’s access to the Black Sea. Speaking to Russian media on December 2, Putin stated, “The most radical solution is to cut off Ukraine’s connection to the Black Sea, thus making piracy impossible in principle.”[14] Putin accused Ukraine of engaging in “piracy” through tanker attacks in the Black Sea and said, “Russia will expand its attacks on Ukrainian ports and on ships entering these ports.” He added, “Tanker attacks become piracy when they are carried out not in international waters but in another state’s, a third state’s exclusive economic zone.”

Ukrainian KAMIKAZE naval-vehicle attacks on Russian oil tankers in the Black Sea constitute a serious violation of freedom of navigation under international maritime law and pose risks of oil spills and environmental pollution.

In response to attacks on tankers, Russia will expand its strikes on Ukrainian ports and on ships entering those ports. “If the attacks continue, we will consider the possibility of retaliatory measures against the vessels of countries that are helping Ukraine carry out these piracy operations.” Putin stated that the Ukrainian leadership and “those standing behind it must reconsider their attacks.”[15]

As the war in Ukraine and shifts in the U.S. approach to European defense unfold, Europe must proactively ensure its own security. Although the precise nature of the U.S. strategic repositioning is still developing, the direction is clear: a greater focus on the Indo-Pacific, and, accordingly, an expectation that Europe will assume a larger share of its own defense burden. In a prepared speech at the NATO Defense Ministers’ meeting in February 2025, U.S. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth emphasized that the United States “cannot be expected to be [Europe’s] permanent guarantor.” The U.S. ambassador to NATO stated in May 2025 that Washington would begin discussions with European allies later in the year on reducing U.S. troop levels in Europe. A new era is beginning in transatlantic relations—one that requires Europe to take greater responsibility for its own security. A new era is beginning in transatlantic relations, and it requires Europe to assume more responsibility for its security.

This represents a structural shift in U.S. foreign policy, driven by a bipartisan focus on China as the primary threat. The possibility of a U.S.–China conflict would strain U.S. resources and limit Washington’s ability to support Europe. Some analyses indicate that the United States would deplete its key munitions—particularly long-range missiles—within just a few days of entering a conflict with China over Taiwan. This would severely limit Washington’s ability to supply certain critical munitions to Europe in the short and medium term. A new era in transatlantic relations is emerging—one that requires Europe to take greater responsibility for its own security.[16]

Achilles’ Shield Project in Greece’s Air Defense

Greek Minister of Defense Nikos Dendias made strong statements in which he identified Türkiye as the “primary threat,” targeting Ankara despite the fact that both countries are NATO allies.[17] Dendias announced that they were undertaking a comprehensive strategic revision for the security of the Aegean Sea and planning to deploy mobile missile units on hundreds of islands.

As tensions continue on the U.S.–European front, Minister Dendias repeated statements targeting Türkiye. Claiming that Türkiye poses a threat to Greece, Dendias asserted that they would deploy missiles on hundreds of islands in the Aegean. Reiterating his claim that Türkiye poses a threat to his country, he said:

“Greece has been living in a contradiction since 1952, when it became a NATO member. The most significant threat to NATO-member Greece comes from another member of the Alliance—Türkiye. Greece is defending itself, while Türkiye is threatening.”

He then stated they would change the traditional doctrine of “the army protects the land, the navy protects the sea, and combat aircraft protect the air,” explaining the main outlines of the new doctrine.

Greek Air Bases and U.S. Bases in Greece

Greek Minister of Defense Nikos Dendias stated: “So far, it is meaningless for the navy to defend the Aegean. New frigates and new warships are extremely expensive assets to operate in a narrow sea like the Aegean and to be exposed to modern threats. A frigate worth 1 billion euros can be destroyed with a UAV that costs a few thousand euros. Therefore, we have completely changed our doctrine. The Aegean will not be protected only by the navy. It will be protected mainly by mobile missile systems deployed across hundreds, if not thousands, of islands. We will close the sea in the Aegean from the land (he refers to the islands). Thus, the navy’s operations will not be limited to this narrow sea.”

“Until today, air defense was provided mainly by the air force. This is not the right answer. Moreover, it is a very expensive answer. Air defense will mainly be ensured through anti-aircraft weapon systems. We are implementing the project we call ‘Achilles’ Shield.’ In this way, not only the sea but also the airspace of the Aegean will be sealed.”

What Dendias refers to in the Achilles’ Shield project involves the deployment of five different types of missile systems on the Aegean islands and near the Greek-Turkish land border. Greece plans to purchase a significant portion of these missile systems from Israel. Dendias also drew attention to Türkiye’s advances in unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), saying they must take precautions in this area: “Until now, the weapon of the soldier in the land forces was the rifle. The weapon of the soldier is now the UAV. The Greek army must swiftly enter the UAV era. Every soldier must receive UAV training. The country that poses the most visible threat to us (meaning Türkiye) produces UAVs. According to the information we have obtained, this country has more than 1 million UAVs ready. We plan to equip all our frigates with the anti-UAV system we successfully tested in a real combat environment in the Red Sea and named ‘Kentavros.’ We will also be able to use this system against UAVs on land, with some modifications. In addition, we aim to create a new force of 150,000 volunteer reservists. Thus, we aim to increase the total number of reservists to 250,000.” [18]

Evaluating the current developments, former NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen warned that if Europe does not increase its pressure on Russia, Ukraine will face a “war that lasts forever” and a slow territorial erosion. [19]

Range of Russia’s 9M Novator and Iskander Missiles

The 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty prohibited both the United States and the Soviet Union from deploying ground-launched missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 km. By 1990, systems such as the Soviet RSD-10 Pioneer (SS-20), the U.S. Pershing II, and the BGM-109G Gryphon, as well as Germany’s Pershing Ia missiles (though not formally part of the INF Treaty), had been withdrawn from service. However, Russia later deployed and tested new missile systems that the United States determined to be in violation of the INF Treaty, leading President Trump to withdraw from the agreement in 2019.

Today, Russia possesses a broad arsenal of cruise and ballistic missiles that it uses extensively in its attacks on Ukraine. It has also deployed S-400 Triumf long-range surface-to-air missile systems and K-300P Bastion-P supersonic anti-ship missiles along its borders and in the Kaliningrad region. These systems allow Russia to threaten NATO assets at distances of several hundred kilometers, giving Moscow the ability to deny NATO forces access to areas along the Alliance’s eastern flank.[20] Through its numerous missile systems, Russia exerts pressure across the European theater of operations.

China, meanwhile, has demonstrated during its 3 September 2025 Victory celebrations that it intends to extend its growing economic and military technological power—ballistic missiles, UAV-equipped aircraft, submarines, and mobile systems—across the Pacific, Indian Ocean, and Middle East regions.

Transatlantic tensions are weakening the strength of the U.S. security guarantee within NATO. Europe remains heavily dependent on the United States, not only for rapidly deployable forces but also for strategic support. In response to the deteriorating strategic environment and the lifting of INF Treaty restrictions between the U.S. and Russia, a number of European states are now planning to acquire or develop strike systems known as “deep precision strike” (DPS) capabilities, designed to hold enemy forces at risk over long distances.

Meanwhile, technological efforts continue at full speed through various programs aimed at improving the speed, accuracy, and stealth of deep-strike weapons.[21] A development related to this objective, the European Long-Range Strike Approach (ELSA), has been launched by selected NATO members to identify defense requirements for conventionally-armed DPS capabilities and supporting technologies such as intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), and to promote their joint development.[22]

In the long term—perhaps within the next decade—mature ELSA projects may allow Europe to assume this burden entirely. In the meantime, Europe’s most important task, alongside developing its own technologies, will be to ensure continued U.S. commitment to the continent’s conventional defense posture. In this context, Boris Pistorius’s interest in U.S.-made strike systems may be an important step toward a new era of U.S.-Europe burden sharing.

The Future of European Missile Defense

However, it may also signal the possibility of a more radical U.S. pullback—one that would require a sudden, unintended, and perhaps unachievable transfer of burdens onto Europe. In 2024, France, Germany, Italy, and Poland launched the European Long-Range Strike Approach to develop a European-made, land-based cruise missile—claimed to have a range of 1,000 to 2,000 kilometers—expected to enter service in the 2030s. Now also joined by Sweden, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, this initiative aims to close an urgent capability gap and to ensure “better burden sharing within the alliance.”

More European long-range strike systems are on the way: the sea- and air-launched variants of the British-French (and Italian) Future Cruise/Anti-Ship Weapon are expected to arrive in 2028 and 2030 respectively. These systems will be capable of striking targets at distances greater than 1,600 kilometers. Meanwhile, the German government is working on the Taurus Neo, a next-generation missile with improved range, accuracy, and explosive power, expected to be fielded starting in 2029.

Despite these latest efforts, Europe’s long-range missile capabilities remain limited. After the Cold War, European states not only abandoned major investments in their armed forces, but they also largely expected their militaries to operate in permissive environments. As a result, air forces prioritized acquiring bombs and short-range missiles with limited explosive power for use against irregular forces in populated areas. In a conflict where operating in an airspace saturated with Russian capabilities is an operational assumption, such weapons will have limited utility.

Russia’s launch of medium-range ballistic missiles against Ukraine has pushed Western states to consider redeveloping IRBMs—systems whose use was banned at the end of the Cold War. The West is taking this threat very seriously. The European Defence White Paper – Preparedness 2030 states: “Europe faces an acute and growing threat. The only way to maintain peace is to be ready to deter those who wish to harm us.” This goal requires practicality. Recent operational experience in Ukraine, Israel, and Pakistan clearly demonstrates the superior techno-operational effectiveness of cruise solutions compared to ballistic ones. This does not rule out ballistic systems entirely; however, given Europe’s urgent need to rearm quickly, at scale, and at acceptable cost, it underscores that developing new ballistic weapons as capable and effective as the cruise systems already in development is not currently feasible.

SOURCE: C4Defence

References

[1] https://warontherocks.com/2025/09/denial-wont-do-europe-needs-a-punishment-based-conventional-counterstrike-strategy/

[2] Mesut Hakkı Caşın: ‘’ İkinci Dünya Savaşı’’, Nobel Kitapevi, Ankara, 2024.

[3] https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/olj/sa/sa_july01ghc01.html

[4] https://www.csis.org/analysis/chapter-6-enduring-role-fires

[5] https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2023/december/war-2026-phase-iii-scenario

[6] https://thegeopolitics.com/european-rearmament-should-ballistic-or-cruise-missiles-be-prioritized/

[7] ‘’Emerging or Evolving Dynamics International Level the Future of the Battlefield’’,

[8] https://rsdi.ae/en/publications/the-menace-from-above-lessons-on-evolving-missile-defense-for-the-gulf

[9] ‘’Ukraine says it sank Russian large landing warship in Black Sea’’, htps://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ukrainian-forces-destroy-large-russian-landing-ship-military-says-2024-02-14/.

[10] https://www.ifc.usafa.edu/articles/institute-of-future-conflict-2026-threat-horizon-report

[11] https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2025/07/09/russian-military-launches-largest-ever-air-attack-on-ukraine-a89737, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-launches-record-728-drones-overnight-ukraines-air-force-says-2025-07-09/https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2025/07/09/russia-launches-massive-overnight-attack-on-ukraine-with-728-drones

[12] https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/putin-says-that-if-europe-wants-war-then-russia-is-ready-2025-12-02/

[13] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/dec/02/witkoff-in-moscow-for-talks-as-putin-claims-to-have-taken-key-ukrainian-city

[14] https://www.bbc.com/turkce/articles/ckglxp8xd05o

[15] https://www.diken.com.tr/karadenizde-vurulan-gemiler-putinden-ukrayna-ve-yardim-eden-ulkelere-misilleme-tehdidi/

[16] https://www.boell.de/en/2025/09/24/getting-out-how-europe-can-defend-itself-less-america

[17] https://avim.org.tr/tr/Bulten/YUNANISTAN-DAN-EGE-YI-FUZELERLE-KILITLEME-PLANI-YUNAN-SAVUNMA-BAKANI-ANKARA-YI-BIRINCIL-TEHDIT-ILAN-ETTI

[18] https://www.hurriyet.com.tr/dunya/dendiastan-tehdit-gibi-aciklama-egeyi-fuzelerle-kapatacagiz-43038100

[19] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/nov/08/russia-ukraine-drone-missile-attacks-energy-infrastructure-casualties

[20] https://icds.ee/en/typhon-an-effective-step-towards-european-long-range-strike/

[21] https://www.ifri.org/en/studies/deep-precision-strikes-new-tool-strategic-competition

[22] ‘’ Deep Precision Strike: Europe’s Quest for Long-range Missile Capabilities’’, November 2025, https://www.iiss.org/globalassets/media-library—content–migration/files/research-papers/2025/11/pub25-124-deep-precision-strike-4.pdf

[23] https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2025/01/10/the-threat-of-intermediate-range-missiles-returns-to-europe_6736893_4.html

[24] https://thegeopolitics.com/european-rearmament-should-ballistic-or-cruise-missiles-be-prioritized/