At the forefront of quietly progressing organized efforts is the fact that the EU Commission will collect final applications on 30 November for a fund of 150 billion euros dedicated solely to defense. Throughout last summer, the purse strings were loosened to support efforts aimed at Europe’s rearmament. Nineteen countries have already submitted letters of intent for this low-interest loan to be made available to SAFE (Security Action for Europe) members. According to a recent brief news report, the United Kingdom also sought to benefit from these extensive opportunities; however, it withdrew after finding the EU Commission’s request for a contribution exceeding 6 billion euros too expensive.

At the end of November, we will witness a new beginning in defense spending and a wave of massive orders. Although December and the start of the new year usually mark a calm period in Europe, it is inevitable that military orders and expenditures will skyrocket in 2026. If the letters of intent from partner countries turn into projects, Poland will be in the lead with its demand of 43 billion euros. It is followed by France, Romania, and Hungary, each with demands exceeding 16 billion euros; among the major countries, Italy ranks last among those above the 10-billion threshold with a demand of 14.9 billion. The remaining 14 countries are as follows: Belgium (8.34), Lithuania (6.38), Portugal (5.84), Latvia (5.68), Bulgaria (3.26), Estonia (2.66), Slovakia (2.32), Czechia (2.06), Croatia (1.7), South Cyprus (1.18), Finland and Spain at the one-billion-euro mark. Only two countries remain below one billion: Greece (790 million) and Denmark (50 million).

Of course, certain criteria must be met. Air defense systems come first, followed by modern munitions and unmanned combat vehicles, which have now become indispensable on the battlefield. Command and communication systems must also be remembered; in line with topics frequently highlighted in the media in recent months, an emphasis on countermeasures against UAVs/UCAVs is expected. In fact, nothing is new in this area; these weapon systems are urgently requested by Western countries. The change here is the encouragement of collective and joint procurement of these products. The additional advantage is that the loans used by many European countries whose debt ratios are at the 3% limit will not be reflected in national debt levels, as the EU Commission allows flexibility on this issue. It will be important to monitor where this process leads in the coming period.

Another major restriction is that 65% of the materials, munitions, and weapon systems to be purchased must be produced in EU countries. Apart from several limitations, countries with Free Customs Agreements and members of the European Economic Area have also been accepted into the procurement system. In addition, Ukraine is granted a special privilege due to wartime conditions. For third countries outside this group to comply with SAFE requirements, they must have signed a joint defense pact with EU states. Norway, South Korea, Japan, Albania, Moldova, and the United Kingdom meet this condition. The military and security procurement projects to be submitted to the Commission at the end of this month must include at least one EU member and be prepared with countries that comply with the restrictions mentioned above.

European Defense Industry Is Growing Rapidly

With new financial opportunities added to the EU and member states’ military procurement processes, the European defense industry has gained strong momentum. Whether it will encourage new investors such as Turkey in the coming years remains to be seen. In fact, the European defense industry ranks second after the United States, which holds a 43% share of global arms sales, with 40% between 2020 and 2024. The Ukraine War and the rhetoric of U.S. President Donald Trump have created global uncertainty within the existing security framework and weakened the concept of U.S. guarantorship. The resulting international insecurity has increased global arms sales, transforming the single-supplier structure into a broad and multi-layered economic system.

Turning to the European continent, over the last five years France’s defense industry—particularly Rafale sales—has ranked first among member states in global arms sales, with a 9.6% share. It is followed by Germany (5.6%), Italy, the United Kingdom, and Spain. Looking at export data retrospectively, Italy has recorded the highest increase in arms sales over the past five years with 138%, followed by Spain with a 23% increase.

The increase in arms purchases stems from a combination of several key factors. For many years, weapon systems and munitions stockpiles dating back to the Cold War were used. As the winds shifted in recent years, the need for modernization of armies has emerged as a stark reality and taken priority. In short, all these orders and recent purchases are not about increasing troop numbers; they are aimed at renewing existing structures and sending political messages to societies. Regarding warfighting capability, army structure and national readiness are measured by military units; qualified military equipment complements them.

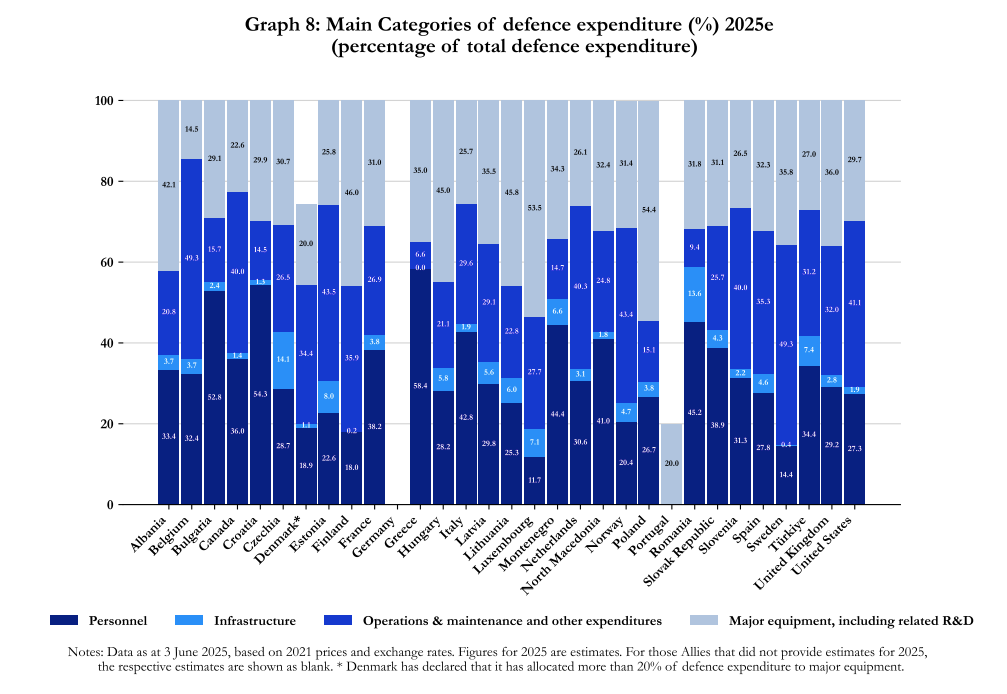

In many NATO countries, if only one corps or 3–5 aircraft squadrons have existed for years, doubling their capacity takes a long time and raises annual costs by 1.6 to 2 times. Moreover, these budgets are already exhausted; creating new taxes is politically difficult. In countries like Turkey, which maintains compulsory military service, or Poland, which has structured its army for large-scale wars, these budgets already exist and continue. If other countries wish to catch up, they must invest five to seven years of time, money, and serious effort in the preparation process. According to 2024 data from the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. is by far the leading country, allocating USD 2,239 per capita. In Europe, those spending over USD 1,000 per capita on defense are generally found only in the north of the continent.

NATO Finances

In addition to national military expenditures, the common expenses arising from allied needs generally remain out of sight. NATO’s annual general costs amount to approximately 4.6 billion euros in 2025, with 5.3 billion planned for the following year. The civilian financial budget under the Secretary-General is projected to be 483.3 million euros in 2025. This civilian budget is generally transferred from foreign ministries and covers salaries, maintenance work, training, diplomatic activities, and various joint projects of the Secretariat for permanently employed civilian and uniformed personnel at the Brussels headquarters or at international locations.

The 2.37 billion euros referred to as the “Military Budget” and managed by the Budget Committee is allocated in the 2025 fiscal year to all military needs of the alliance, especially the maintenance of jointly used defense and weapon systems, including military bases. Furthermore, investments aimed at enhancing deterrence—such as building, integrating, and maintaining joint security and defense systems (NSIP)—are generally linked to Ministries of Defense. A total of 1.723 billion euros has been allocated in this area for the 2025 fiscal year, overseen by the NATO Investment Committee. In addition, special joint budgets are created for NATO’s common defense industry programs, and committees and oversight mechanisms involving contributing countries are established.

Payments are determined by a burden-sharing system across the 32 member states and two-year budget programs. Turkey’s current share of 4.5927% will rise to 6.3010% in the 2026/27 fiscal period, and Turkey will host next year’s NATO Summit. While the largest contribution is made by the U.S., the Trump administration has requested a reduction and an equalization with Germany’s share, contrary to previous years. Thus, in 2025, the U.S. and Germany will both hold the top position with contributions of 15.8813%, followed by the United Kingdom (10.9626%) and France (10.1940%).

As the fiscal year ends and the new 2026 budgets are debated, my purpose in sharing some military budgets is to remind that the issue is not the lack of money for armies—as frequently discussed these days—but that correct guidance is more crucial than ever. When defense expenditures of NATO countries are analyzed individually, the proportional importance of personnel and maintenance costs stands out.

Europe has entered a phase of war preparation; its priority seems to be securing financing and encouraging industrial investments. The truly difficult part is rebuilding the force structure, rapidly doubling the small number of trained officers and NCOs, and then finding the personnel to form the companies and battalions that constitute the actual structure. This will only be possible with momentum that begins with the involvement of society. We will frequently see European countries take steps in this direction in the coming years.

For now, the defense industry has gained great momentum in EU economies; whether their revenues will increase and be redirected toward reinvestment is something we will see over time. It should be assumed that new loans and financial opportunities will increasingly be allocated to the defense sector, and countries must prepare for intense competition.

I would like to emphasize once again that Europe’s and NATO’s defense cannot be ensured solely through industry. Army structure is measured by the organization of military units; military technological equipment provides additional strength.

There are many unknowns on the battlefield. The advantages that robotic systems—such as UCAVs and UAVs—will provide on the new battlefield are so significant that they will force doctrinal changes. Let us not deceive ourselves; newly developing “innovation” weapon systems fill gaps or replace existing structures.

The human element of a nation, however, still retains its indispensability on the battlefield.

Preventing wars depends on deterrence during peacetime, and as a nation, we must always be prepared…

SOURCE: C4Defence