“The ‘Pax Americana’ that has endured in Europe, and in Germany as well, for decades has largely come to an end for us.”

German Chancellor Friedrich Merz[1]

INTRODUCTION

The new U.S. National Security Strategy (NSS) prepared by the administration of U.S. President Donald J. Trump represents a clear break from previous versions and conveys important messages about how U.S.–European relations are changing in real time within American foreign policy. At its core, the new strategy aims to bring the Russia–Ukraine War to an end—viewed through the lens of the United States as a victor of the Second World War and Russia as the successor state to the former enemy, the USSR—and to terminate warfare on the European continent in order to establish a broader strategic stability.

According to the definition set out in the National Security Strategy, “the days when the United States upheld the entire world order like Atlas have come to an end.” Instead, the Trump administration defines the Western Hemisphere as America’s primary strategic focus, while leaving China and Russia largely to their own spheres of influence. However, the most fundamental rupture outlined in the strategy occurs in America’s relationship with Europe. The picture drawn by the new U.S. National Security Strategy (NSS) with regard to the continent is bleak.

The new National Security Strategy—described as a definitive break from the post-1945 order first shaped by Harry Truman and nurtured by every successive U.S. president up until Trump—signals a dramatic departure from decades of U.S. foreign policy. Normally, the announcement of a new National Security Strategy is a highly significant event. Josep Borrell, former high-ranking diplomat of the European Union, has described this divergence—which effectively places a time bomb under the transatlantic bridge between the U.S. and Europe—as a “declaration of political war.”

The new U.S. National Security Strategy has been interpreted by some diplomats as meaning that “the Western alliance has ended; relations will never be the same again.” [2] Trump’s America is not merely indifferent to Europe; it is openly hostile toward it. This has enormous consequences for the continent and for the United Kingdom, yet many leaders still refuse to acknowledge it. Defenders of Trump have tried to argue that the administration does not have a problem with Europe itself, but rather with the European Union. [3]

In this context, the NSS truly represents a dramatic shift in the direction of U.S. foreign policy and may have potentially serious consequences for transatlantic relations with Europe. On the one hand, despite the threat posed by Russia, the NSS clearly demonstrates that Europe’s defense has declined as a U.S. priority. On the other hand, it explicitly states that Europe must take care of its own defense and that there will be no further NATO enlargement—meaning no NATO membership for Ukraine.

This approach is, in some respects, not entirely surprising. The strategy effectively amounts to a declaration of war on European politics, European political leaders, and the European Union. [4] At the same time, it seeks to reorder relations between the United States and Russia—a country that possesses the world’s largest nuclear arsenal and all the natural resources known to humanity. This signals Washington’s intention to reduce tensions with Moscow, viewing Russia not as an existential enemy, but as a nuclear power with which “strategic stability” must be restored in order to prevent sudden escalation. [5]

On the other hand, another point of divergence is the NSS’s insufficient focus on great-power competition. In the document, China is mentioned for the first time only in roughly the final two-thirds of the text. Russia, rather than being portrayed as a revisionist power, is framed as an existential concern for Europeans and as an issue perceived as potentially leading to war. In the face of this danger, the United States—despite being a NATO ally—is not defined as a party to a potential Europe–Russia conflict, but rather as a mediator tasked with preventing it.

This approach, both in practical and theoretical terms, constitutes a call by the U.S. administration for a reset in transatlantic relations. Unlike other regions, Europe is addressed explicitly in ideological terms, and the strategy argues that the restoration of “Europe’s civilizational self-confidence and Western identity” is a critical element of any continuing partnership. The document treats Europe’s domestic politics as a key variable: it accuses the European Union’s migration policies of “transforming the continent,” condemns international regulations that “undermine political freedom and sovereignty,” and warns against censorship regimes that “suppress political opposition” and erode freedom of expression.

Trump claims that the future of the alliance depends on a fundamental transformation in Europe’s domestic politics, aligning governance practices more closely with the priorities of the American right. At the same time, by demanding a structural change in Europe’s role within the alliance system, the administration insists that European states “assume primary responsibility for their own defense,” abandon expectations of an ever-expanding NATO, and meet a significantly higher standard of defense spending. [6]

The administration is attempting to define an extremely pragmatic, and perhaps short-sighted, new “America First” foreign policy doctrine. For example, the democracy agenda has clearly come to an end. As this brief analysis demonstrates, the Trump administration’s 2025 National Security Strategy is unprecedented in many respects in U.S. history. Essentially, most strategy documents of this kind articulate the threats posed by America’s adversaries to Washington and its allies and explain how officials might respond to these challenges. This document, however, appears to treat U.S. adversaries more gently than its friends. It criticizes Europe with striking candor, arguing that some of the continent’s domestic policies undermine democracy and lead to the “destruction of civilization.” [7]

1. Signals of Change in Collective Security Theory

Less than a year into Donald Trump’s second term, transatlantic relations have taken on a markedly different character. A complete rupture between the United States and Europe has not occurred; however, transatlantic trust has been shaken. We now have to move forward in an environment of low trust.

The NATO Hague Summit demonstrated a renewed commitment to transatlantic security, with member states pledging historic increases in defense spending and endorsing a broader vision of resilience encompassing cyber, infrastructure, and societal domains. This shift represents more than mere adaptation; it signals a serious intent to rearm NATO for a new era of strategic competition. The commitments made in The Hague are only as meaningful as the frameworks and alignment that translate them into collective readiness.

The challenge is not only whether NATO possesses sufficient resources, but also whether it can effectively align them across national priorities, operational plans, and strategic objectives. Without clarity of purpose, institutional flexibility, and cohesion among allies, even historically high levels of military spending risk falling short.

Meanwhile, adversaries are not waiting. Despite all the declarations made in The Hague, fundamental questions remain unresolved: Does NATO appear more secure after the summit, or merely more expensive? Is the alliance designing a future-oriented security architecture, or is it simply reacting in a largely formal manner, still without full strategic coherence? NATO’s credibility over the next decade will depend not only on funding, but also on its ability to think ahead, make rapid decisions, and act with the consistency required to deal with adversaries who do not wait for deterrence to take effect. [8]

As is well known, the traditional concept of collective security—most clearly exemplified by the League of Nations established after the First World War—aims to move beyond power politics by committing states to resolve their differences through peaceful means and to work together to stop any country that violates this principle. The final and most effective form of collective security—more accurately described as “collective defense”—is the military alliance. States facing a common threat can make themselves more secure by agreeing to assist one another in defense and by coordinating their military preparations to deter a threatening state from attacking or to defeat it if it does.

Alliances are most likely to form when a powerful and well-armed state is nearby and appears willing to use force to alter the status quo. In such cases, the threat posed by the potential aggressor will be clear to others and will provide sufficient reason for them to unite against the danger. This logic explains why NATO was established in 1949; why the United States formed alliances with Japan, South Korea, and other Asian states during the Cold War; and why a large coalition came together in the First Gulf War to expel Iraq from Kuwait. [9]

On the other hand, since the Second World War, Europe has depended on the United States for many of its security guarantees. Within this NATO-organized framework, all willing allies and reliable partners can contribute to the production of equipment and capabilities, while military training and enhanced exercises can prepare all NATO members and trusted partners for collective defense against attacks of varying intensity.erini savunmaya yardım etmeyi ve tehdit eden bir devletin kendilerine saldırmasını engellemek veya saldırırsa onu yenmek için askeri hazırlıklarını koordine etmeyi kabul ederek kendilerini daha güvenli hale getirebilirler. İttifaklar, güçlü ve iyi silahlanmış bir devletin yakınlarda olduğu ve statükoyu değiştirmek için güç kullanmaya istekli göründüğü durumlarda oluşma olasılığı en yüksektir . Bu durumda, potansiyel saldırganın oluşturduğu tehdit diğerleri için açık olacak ve onlara tehlikeye karşı birleşmek için yeterli sebep verecektir. Bu mantık, NATO’nun 1949’da neden kurulduğunu; Amerika Birleşik Devletleri’nin Soğuk Savaş sırasında Japonya, Güney Kore ve diğer Asya devletleriyle neden ittifak kurduğunu ve büyük bir koalisyonun ilk Körfez Savaşı’nda Irak’ı Kuveyt’ten çıkarmak için neden bir araya geldiğini açıklamaktadır. [9] Öte yandan, İkinci Dünya Savaşı’ndan bu yana Avrupa, birçok güvenlik garantisi için ABD’ye bağımlı olmuştur. NATO tarafından organize edilen bu yapıda, istekli tüm müttefikler ve güvenilir ortaklar ekipman ve donanım üretimine katkıda bulunabilirken, askeri eğitim ve artırılmış tatbikatlar, tüm NATO ülkelerini ve güvenilir ortaklarını çeşitli şiddetteki saldırılar karşısında ortak savunmaya hazırlayabilir.

The NATO Hague Summit and the 5% Defense Spending Commitment

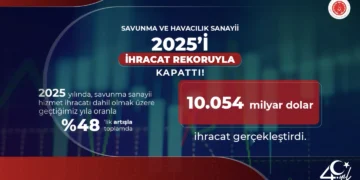

In light of these statements, the National Security Strategy (NSS) clearly declares that the era in which the United States “supported the entire world order like Atlas” has come to an end and demands that Europe pay far more for its own security. It welcomes the “Hague Pledge,” under which NATO allies have committed to spending 5 percent of their GDP on defense by 2035, and states that the United States will now “build a burden-sharing network” so that “all of our efforts benefit from broader legitimacy.”

In practical terms, this means that the United States will provide assistance—through trade advantages, technology sharing, arms sales, and similar instruments—only to allies that assume greater responsibility for regional security. As the strategy puts it, the United States is prepared to reward “countries that voluntarily assume greater responsibility for security in their neighborhoods.” This emphasis on allied defense spending and “primary responsibility” echoes and reinforces earlier U.S. pressure on Europe. During the 2017 National Security Strategy, the Trump administration for the first time made NATO burden-sharing a priority, and subsequent administrations (Obama and Biden) also pushed allies to meet the 2 percent guideline. The 2025 NSS doubles down on this approach: allies must commit to 5 percent, or face diplomatic consequences.

Analysts at the Atlantic Council note that “throughout 2025 … the administration’s objective in Europe is to shift the burden of conventional defense onto the shoulders of European allies.” At last year’s NATO summit, the United States secured a defense commitment of 5 percent of GDP; however, as Atlantic Council analyst Torrey Taussig observes, “the NSS does not help further advance U.S. national security interests on the European continent.” Critics warn that this approach could weaken assurances, particularly on NATO’s eastern flank. For example, allies view Russia as a genuine threat, and Washington’s focus on burden-sharing without an equally strong emphasis on collective defense may undermine Europe’s confidence in U.S. commitment. [10]

French President Emmanuel Macron’s famous 2019 remark about NATO’s “brain death” may have been exaggerated. Nevertheless, prior to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s fateful decision to invade Ukraine in 2022, the Atlantic Alliance was clearly undergoing a recurring cycle of self-criticism. President Macron was primarily referring to disagreements over Middle East policy. At the core of the crisis, however, were unprecedented questions about the United States’ commitment to European security, as well as a growing tendency in Washington and other NATO capitals to pursue national agendas at the expense of transatlantic cohesion. NATO’s much-debated “raison d’être” question—first raised after the fall of the Berlin Wall—had once again returned to the agenda.

Looking ahead to 2025 and beyond, NATO’s recent and undeniable successes do not necessarily point to a clear and stable future path. At the very least, the Alliance must avoid complacency as it confronts a range of new challenges. In particular, with Donald Trump’s return to the White House and his plan to double down on the “America First” agenda, the credibility and durability of U.S. commitment have once again become a major source of concern. Recent statements regarding Canada, Greenland, and Panama illustrate the potentially disruptive approach the U.S. president may adopt toward key relationships. While it is true that President Trump did not withdraw entirely from NATO during his first term and even increased America’s contributions to European security, his transactional and emotionally detached approach to the Alliance risks further eroding its most vital asset: trust. [11]lir.[11]

2. Where Is the West on the Compass of the New U.S. National Security Strategy?

The strategy points to economic stagnation in Europe, attributing it primarily to the European Union’s stifling regulations and criticizing insufficient military spending. However, the picture is portrayed as even more dire. The NSS warns that Europe’s economic decline is being overshadowed by the “real and far more serious possibility of the collapse of civilization.” Among the larger challenges facing Europe, the document lists the actions of the European Union and other supranational organizations that undermine political freedom and sovereignty; migration policies that transform the continent and generate conflict; the censorship of freedom of expression and the suppression of political opposition; declining birth rates; and the loss of national identities and self-confidence. [12]

U.S. policymakers increasingly believe that Europe must take responsibility for its own security so that Washington can focus on constraining Chinese power in Asia. Europe and the United States are also diverging more and more over what should be done in the Middle East. The U.S. National Security Strategy suggests that Washington aims to “reduce its contributions to Europe’s conventional deterrence,” shift its forces to the Indo-Pacific, and “take on risk” elsewhere. At the same time, the strategy contains several shared objectives: resolving conflicts, combating migration, and ensuring economic security. [13]

- What are the shared values and intersecting strategic interests that still bind the United States and Europe together?

- Is the U.S. National Security Strategy, in all its dimensions, coherent and appropriate in scope for developing diplomacy, military power, and economic strength in order to advance American interests?

- Can Washington truly be the savior of civilization?

- Like Mikhail Gorbachev’s “Glasnost–Perestroika” model, which once promised change to the people of the USSR, does this new document have the capacity to launch the “Golden Age” that Trump promises the American people—making America safer, wealthier, freer, greater, and stronger than ever before?

- Is NATO, one of the most powerful alliances of modern times, weakening?

- Can NATO survive solely as an alliance of interests?

- What plans is the United States preparing for the future in the Asia-Pacific against Russia and China?

- How can Europe reconcile America’s increasing focus on the Pacific region and the Gulf of Mexico—within the China–Japan–Russia triangle and with regard to Venezuela—with Europe’s own urgent Eurasian and Mediterranean challenges?

- Can this new strategy document be read as an attempt to frighten Europe and force it toward the Pacific?

- Is the primary objective to retreat behind the Monroe Doctrine, target Nicolás Maduro, and bring regional oil resources under control in order to prevent China from focusing on Latin America?

The Monroe Doctrine and the “Trump Addendum”: The Primacy of the Western Hemisphere

In the U.S. National Security Strategy document, the fundamental and vital national interests of the United States—articulated through answers to the question of “what America wants from the world”—are defined as follows: orienting the strategic compass toward the “Western Hemisphere” and asserting the application of a “Trump corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine; supporting allies in protecting Europe’s freedom and security and restoring Europe’s civilizational self-confidence and Western identity; preventing a hostile power from seizing control of the Middle East, its oil and gas resources, and its strategic chokepoints, while avoiding the “endless wars” that have trapped the United States in the region at great cost; and ensuring that U.S. technology and U.S. standards—especially in artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and quantum computing—drive global progress. [14]

As a “Trump addendum” to the Monroe Doctrine, the strategy states that the United States will work to “reestablish its primacy in the Western Hemisphere.” This idea is fundamentally defensive in nature: forward engagement to prevent uncontrolled migration and to stop “extra-hemispheric rivals” (namely China, Russia, and Iran) from acquiring critical regional assets or basing capabilities that could threaten U.S. territory. However, perhaps the most striking aspect of the new National Security Strategy—despite its stated ambition to think beyond Europe—is its depiction of Europe as a continent in steep decline. [15]

The National Security Strategy (NSS) even claims that “within at most a few decades, a majority of some NATO members will consist of non-European countries,” implicitly suggesting that they could shift from allies to adversaries. It argues that the United States should assist by “cultivating resistance within European countries to Europe’s current trajectory.” Although not stated explicitly, the language of the document implies that “strategic stability with Russia” is part of the solution. In a passage that could have been drafted by the Kremlin, the document asserts that the current problem is that “a large majority in Europe desires peace,” but that this is being “suppressed by unstable minority governments.”

Notably, the document contains not a single criticism of Russia for its openly aggressive war against Ukraine. Unlike the first Trump administration’s 2017 strategy, which was explicit about the Russian threat, the current strategy does not even mention the United States’ commitment to NATO’s Article 5. [16] The document’s limited references to China—solely as an economic competitor—also abandon the president’s 2017 strategy, which labeled both Russia and China as “revisionist powers” seeking to “undermine U.S. influence.”

For those who place the U.S.–Europe relationship and commitment to democratic values at the center of collective security arrangements, the new strategy makes for unsettling reading.

At its core, a security strategy is both a public messaging document and a set of bureaucratic guidelines. It does not constrain the president’s decision-making; rather, it is constrained by the president’s decisions. For this reason, few administrations have adhered strictly to the letter of such texts. Moreover, all such strategies are vulnerable to being rapidly overtaken by events.

Trump has shattered the illusion that what are regarded in Europe as “shared values” are truly shared. It appears that many of these predominantly liberal, left-wing, and far-left values are not embraced by everyone. The emphasis placed on multiculturalism, Willkommenskultur (the German term referring to a welcoming culture, particularly toward refugees), excessive political correctness, and gender issues has created a rift—and this deep division exists not only between Europe and the United States, but also within Europe itself.

Smaller European countries (such as Hungary or Slovakia) and non-mainstream parties (such as France’s National Front, Poland’s PiS, or Germany’s AfD) that oppose Willkommenskultur and European federalism and instead advocate a “Europe of nations” can be ignored or dismissed as marginal. Trump and the American right, however, cannot be ignored. This divide is real, and it runs straight through the heart of most Western societies.

Trump has also made it clear that Europe’s strategic holiday is over. The continent must now pay the full price for its own defense and nearly the full price for its support of Ukraine as well. So far, in both cases, Europe has largely talked the talk but failed to act. Trump may ultimately teach Europe to act—or, if it cannot act, at least force it to stop dreaming and preaching.

NATO 1949-2025

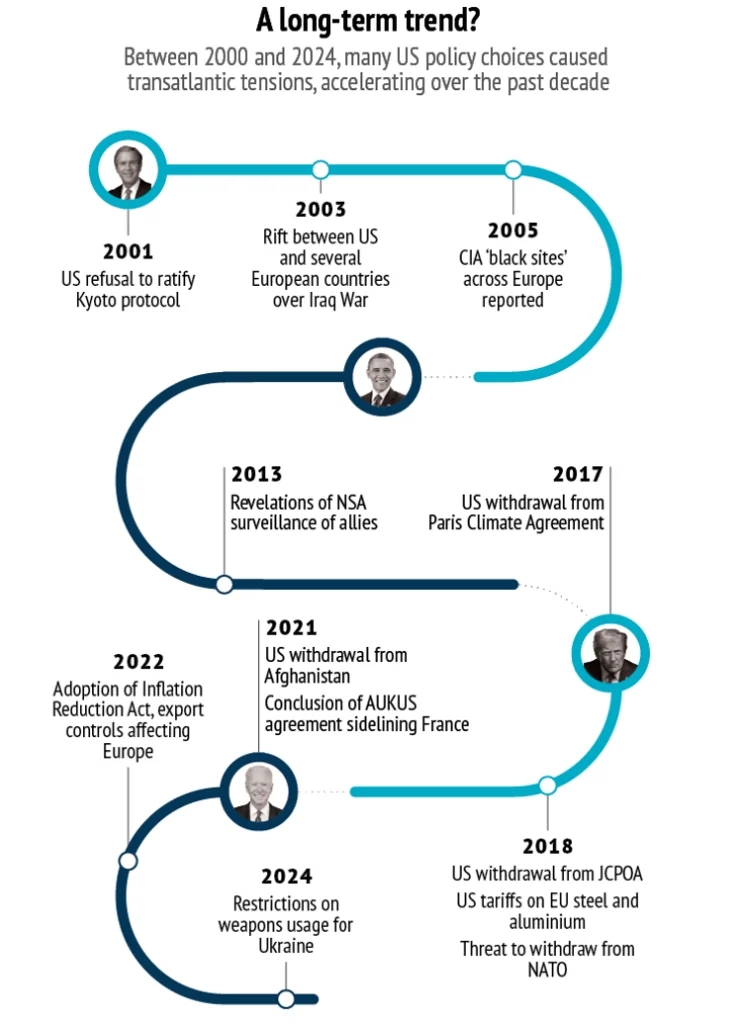

For eighty years, supporting the legitimacy, integration, and security of European democracies has been among the core objectives of U.S. foreign policy. Trump questioned this commitment during his first term and took additional steps in his second. The United States is not merely seeking to rebalance by distancing itself from Europe—a long-standing trend in U.S. foreign policy that predates Trump but has been accelerated by the new White House. This administration has also displayed elements of active hostility toward the European project itself.

Trump has described the EU as a globalist entity that seeks to “exploit” the United States while benefiting from American protection. He has refused to rule out the use of force to annex Greenland, an EU member state and a NATO ally. At the Munich Security Conference, Vice President Vance characterized efforts to combat disinformation as a greater threat than Russia and China. In May, the State Department issued a memo accusing Europe of “waging an aggressive campaign against Western civilization itself.” In August, the State Department instructed U.S. embassies in Europe to actively oppose EU regulations on digital services.

Careful diplomatic engagement by European leaders persuaded the president to step back from one of these excesses. After allies pledged to spend 5 percent of GDP on defense, he altered his rhetoric on NATO, declaring that the alliance was “not a rip-off.” [17] The National Security Strategy (NSS), invoking the Declaration of Independence—particularly the idea that all nations have the right to a “separate and equal station” vis-à-vis one another—suggested that the Trump administration would similarly pursue a policy of “non-interference in the affairs of other nations.” The document states that the administration “will seek good relations with the nations of the world, but will not impose democratic or other social transformations that differ greatly from their traditions and histories.”

Since the Cold War, the region had been relegated to secondary importance, first overshadowed by the Middle East and later by the Indo-Pacific. This time, however, the Western Hemisphere takes center stage in the National Security Strategy, ahead of Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. The goal for the Western Hemisphere is ambitious: to “reestablish American primacy.” Does the National Security Strategy reject American primacy, or merely the liberal values that once guided it? The answer is the latter. Trump’s National Security Strategy (NSS) does not seek liberal primacy; it advocates civilizational primacy instead.

By warning that Europe faces the “destruction of civilization” due to migration and “declining birth rates,” the strategy accuses the European Union (EU) and other supranational institutions of eroding freedom, undermining sovereignty, and stifling creativity and industriousness. [18]

The current Trump administration’s new National Security Strategy departs from the explicit focus on great-power competition shared by the previous two administrations. Both the first Trump administration and the Biden administration framed China’s and Russia’s desire to “shape a world contrary to U.S. values and interests” as a leading foreign policy concern. China was treated as a long-term “pacing power” in the global competition for influence, while Russia was addressed as an “acute threat” actively engaged in “disruptive activities and aggression.”

By contrast, the new National Security Strategy (NSS) makes no explicit reference to great-power competition at all. Instead, it adopts a markedly more conciliatory tone toward rivals, framing the challenge as “managing Europe’s relationship with Russia” and “rebalancing America’s economic relationship with China.” At the same time, it presents the “outsized influence of larger, wealthier, and more powerful nations” as a “timeless reality of international relations,” thereby steering the United States toward rejecting the “unfortunate concept of global dominance” in favor of “global and regional balances of power.”

What this implies is that the United States is less focused on strategic competition and more open to spheres of influence. This may help explain why, aside from a peculiar fixation on Europe’s “civilizational self-confidence,” the new NSS is overwhelmingly focused on the Western Hemisphere, trade, migration, and other issues closer to home. Indeed, the strategy repeatedly declares that the United States will “defend its sovereignty” and will treat alliance members fairly, rather than serving as a permanent security safety net for them.

For example, the National Security Strategy promises to reform or resist international institutions that constrain U.S. freedom of action, pledging protection against the “sovereignty-eroding assaults of the most intrusive transnational organizations.” This ideological framework makes explicit what previous strategies only implied. Appeals to shared liberal values are gone; instead, the National Security Strategy condemns “elite-driven, anti-democratic restrictions on fundamental freedoms” among allies. Even issues such as migration are framed in terms of sovereignty: the United States seeks full control of its borders and calls on “sovereign countries… to stop, rather than facilitate, destabilizing population flows.” [19]

Today, power is no longer projected and consumed primarily in tangible territorial space, but rather in abstract domains such as data, standards, platforms, and systems. In this environment, the United States no longer views the provision of a large and permanent military presence in Europe as inherently beneficial. What once underpinned influence and deterrence is now seen as tying resources to a domain where marginal returns are diminishing while escalation risks are increasing. The emerging logic favors selective engagement and the use of leverage at a distance. Complexity is being replaced by optionality.

This does not, however, amount to withdrawal. Europe remains critically dependent on the United States in the abstract domains that shape power. American firms dominate the data infrastructures that underpin everything from European cloud services and digital platforms to artificial intelligence development, cybersecurity ecosystems, and databases supporting finance and defense logistics. While Europe’s diversification efforts remain incomplete, regulatory initiatives aimed at penalizing U.S. firms for their entrenched market power are increasingly interpreted in the United States not as competition policy, but as geopolitical confrontation. Growing hostility toward Brussels among segments of Silicon Valley reflects where real influence is perceived to lie.

Energy policy tells a similar story. The United States is rapidly entrenching itself as the dominant LNG supplier to Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe—including Ukraine—through terminals in Poland, Lithuania, Croatia, and Greece. The revitalization of the Three Seas Initiative (3SI) framework and the P-TEC format serves this purpose well. U.S. LNG is replacing Russian pipeline gas, but if geopolitical instability in the region becomes unacceptable, American firms can redirect cargoes globally, allowing Washington to support allies remotely without deploying ground forces. [20]

3. Reading the New Security Shift Through the Lens of European Allies

In fact, a crucial point that should not be overlooked is Trump’s unpredictability when it comes to transatlantic relations. In response to his conciliatory approach toward Putin and Russia, and his predominant focus on China, European leaders are being driven to prepare responses to a partial U.S. withdrawal.

The NSS clearly reveals that the United States does not share a common threat perception with its NATO allies. In a striking reversal of priorities compared to the first Trump administration’s NSS, the latest document devotes far more attention to what it defines as Europe’s internal threats—stemming from the European Union’s excessive regulation, censorship, and the “destruction of civilization”—than to the threat of Russian aggression, which is largely absent from the text. [21]

The National Security Strategy constitutes a real, painful, and shocking wake-up call for Europe. It marks a moment of profound divergence between how Europe sees itself and Trump’s vision of Europe. If Europe had any doubts about whether the Trump administration was fully committed to its strategy of “tough love,” those doubts should now be dispelled. The most troubling sections of the strategy are those that accuse Europe of losing its European character. The sentiment behind these words appears to fuel fear of immigrants and, at best, a questionable attachment to an idealized old-world Europe. [22]

The NSS’s call for a rapid ceasefire ignores the fact that it is Russia that has obstructed such an outcome. Pressuring a country that is the victim of Russian aggression implies that the United States may be prepared to accept Ukraine—and Europe’s immediate neighborhood—falling within Russia’s sphere of influence. This carries dire consequences for NATO’s newer members, for whom Russian aggression is seen by the Kremlin as one of the “root causes” of the war. The outright rejection of further NATO enlargement appears less like a strategic declaration and more like a tactical signal to Moscow in the context of ongoing negotiations. Codifying this position in an official document amounts to a gift to Russia, offered without receiving anything in return.

The NSS also seeks alignment with a right-wing populist international force whose influence on European politics is growing, but which remains problematic for the majority of governments and voters on the continent. The condescending tone toward the EU is counterproductive. At the same time, the diagnosis of economic stagnation, technological lag, and integration challenges is partly accurate. Europe must take its own weaknesses seriously, without allowing external powers to dictate its future course.

Finally, the National Security Strategy defines Latin America as an exclusive U.S. sphere of influence. By definition, this approach does not seek the consent of the countries concerned and runs counter to European approaches that, in principle, reject spheres of influence. [23] Likewise, by designating its own hemisphere as the priority region, Europe is relegated to a lower tier. Even this alone should be enough to capture Europe’s attention.

Europe began to take action after Vance’s Munich speech, approving a €150 billion credit facility to develop missile defense, cyber, and unmanned aerial vehicle capabilities. Brazil, seeking to limit its dependence, has moved away from the United States by prioritizing more diversified trade relationships. Such steps—for Europe and beyond—have now taken on greater urgency.

The U.S. strategy will not be implemented overnight. Because attention may shift elsewhere, its core elements may never be fully realized. Yet it nonetheless offers a definitive—if contradictory—road map for understanding and managing the next three years under the Trump administration. Whether this reflects reality or merely aspiration remains unclear, but the United States appears to be moving away from the Atlantic—sliding down a slope toward a sea of transactional deals with autocrats and an easier path of engagement. [24] Allies shaken and often unsettled by Washington’s heavy-handedness have nonetheless not turned away from the world’s most powerful superpower. [25]

Three questions shape Europe’s response: How does the National Security Strategy (NSS) redefine the Russian threat? What does it mean for U.S. support for Ukraine? And how does it reshape transatlantic alignment in a more fragmented world order? Taken together, the answers reveal the deepest divergence in transatlantic threat perceptions since the end of the Cold War. Europe now faces a more difficult phase in the relationship—one in which responsibilities increase while influence narrows. The divergence is not only about priorities, but also about the nature of the threat itself.

If the new U.S. National Security Strategy contains one message that unsettles Europe’s frontline states, it is its reframing of Russia. Rather than presenting Moscow as the primary strategic adversary whose long-term intentions define Europe’s security environment, the NSS treats Russia largely as a challenge that can be mitigated through renewed diplomatic engagement and efforts to restore “strategic stability.” For countries living on the front lines of Russian pressure, this marks a significant departure from previous U.S. strategies and exposes a deeper divergence in how the two sides understand the nature of the threat.

Equally striking is the elevation of Europe’s internal vulnerabilities—rather than Russian aggression—as the more consequential long-term threat to stability. In the National Security Strategy, issues such as demographic decline, pressures on social cohesion, regulatory stagnation, and institutional strain are identified as the core risks to Europe’s future. While these challenges are real, this framing diverges sharply from the Baltic perspective, which for two decades has guided resilience-building efforts on the understanding that internal strength and external deterrence are inseparable. [26]

According to the assessment of Alexandra de Hoop Scheffer, President of the German Marshall Fund of the United States, Europe needs to do three things simultaneously. First, it should continue partnering with the United States where interests overlap. Second, where interests diverge, Europe will need to act on its own. Third, Europe must build alliances with other like-minded powers. This has already been evident in recent months in the Indo-Pacific, as well as in relations with countries in the Middle East and Latin America. What we are witnessing today, therefore, is a new transatlantic bargain in which Europeans have accepted and internalized the idea that the transatlantic relationship will be more transactional and conditional. This includes collective defense. For this reason, the time has come for Europe to act to preserve the transatlantic bond while simultaneously reducing its strategic dependencies on the United States. [27]

From an international relations perspective, the most profound change Trump has brought about in Europe has been the destabilization of the U.S.–European partnership. Over the course of Trump’s two presidencies, the bloc has come to realize that the United States is no longer a reliable and close partner. Trump has eroded the most important political capital in transatlantic cooperation: trust—the cornerstone of the post–Second World War partnership between the United States and Europe. The regional security pact at the core of NATO has been seriously weakened, damaging Karl Deutsch’s famous concept of a “security community” built on shared values and a sense of “we-ness.”

As a result, Europe must rapidly rethink its security architecture and take more independent steps. [28] For the Baltic states, Germany, Poland, and much of Central and Northern Europe, Russia constitutes an existential threat, and they are rearming accordingly. For others, Russia remains a problem to be managed and does not necessitate a fundamental shift in security policy. Inevitably, security will be tightened first where the threat is most acute, and regional ties are strengthening. It is no coincidence that Poland has chosen Swedish submarines for its naval rearmament program, or that Norway has opted for British frigates and German submarines.

Previous strategies portrayed China as the principal existential rival, and Europe was expected to align with this approach in its risk-reduction efforts. The 2025 National Security Strategy is far more transactional in nature: it calls for a “genuinely mutually beneficial economic relationship with Beijing” and envisions a future in which the United States possesses an economy growing from $30 trillion to $40 trillion, while continuing to trade with China in “non-sensitive sectors” such as consumer goods.

The “mutually beneficial economic relationship” that Washington seeks to establish with Beijing, however, is not extended to Europeans. Instead, the National Security Strategy (NSS) encourages Europe to confront Beijing by pushing back against “mercantilist overcapacity, technology theft, cyber espionage, and other hostile economic practices.” If U.S. security guarantees are relaxed in these bilateral arrangements, Europe’s leverage over China will weaken, leaving Europeans to fend for themselves. [29]

The U.S.–European peace plan prepared to deter future Russian attacks on Ukraine предусматривает a stronger Ukrainian military, the deployment of European forces inside the country, and expanded use of American intelligence. These details were shared by officials familiar with draft versions of the plan. According to statements made both publicly and privately, American and European diplomats who met with Ukrainian leaders in Berlin largely signed two documents outlining security guarantees. These security documents are designed as the cornerstone of a broader agreement aimed at achieving a ceasefire to end nearly four years of conflict. They also seek to persuade Ukraine to make territorial concessions in a peace settlement and to forgo formal NATO membership.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen stated, “We are seeing real and tangible progress. This progress is made possible by alignment between Ukraine, Europe, and the United States.” [30]

4. A New Global Disorder Centered on the Ukraine–Russia War

On Ukraine, the 2025 National Security Strategy (NSS) defines the end of the war as a “core interest” for the United States. The strategy calls for “the rapid end of hostilities in Ukraine in order to stabilize European economies, prevent unwanted escalation, and reestablish strategic stability with Russia.” In other words, the U.S. objective is a negotiated freeze or settlement that would ensure Ukraine’s survival while halting the fighting. This formulation contradicts the United States’ previous commitments to Ukraine. In short, the 2025 National Security Strategy reorganizes transatlantic relations along transactional and nationalist lines. It envisages a tougher bargain for Europe: paying more for defense, taking control in Ukraine, liberalizing trade in America’s favor, and even abandoning some common EU policies. Although the strategy still acknowledges Europe’s value—“American diplomacy should continue to unapologetically celebrate real democracy, freedom of expression … and the individual character and history of European nations”—it is clear that America now sees Europe as an important but unequal partner. As one European commentary notes, alliances are “mutually reinforcing processes,” but only the strong can negotiate them to their advantage.[31]

If the new U.S. National Security Strategy contains a single message that unsettles Europe’s frontline states, it is its approach to Russia. Rather than presenting Moscow as the primary strategic adversary whose long-term intentions shape the European security environment, the National Security Strategy treats Russia as a challenge that can largely be mitigated through renewed diplomatic engagement and efforts to restore “strategic stability.” For countries living on the front lines of Russian pressure, this marks a significant departure from previous U.S. strategies and reveals a deeper divergence in how the two sides understand the nature of the threat.[32]

Although peace in Ukraine remains an elusive prospect, officials are discussing what the postwar security environment might look like once the guns fall silent in Europe’s deadliest conflict since World War II, due to signs of progress from the White House’s diplomatic initiatives. However, far from ushering in a new era of stability and calm on the continent, the next chapter will be dominated by a new type of warfare already unfolding across many unconventional fronts, ranging from unmarked drones and hard-to-trace cyberattacks that penetrate NATO defense lines to the growing popularity of political parties sympathetic to Moscow. This was partly driven by dissatisfaction over mass migration, some of which originated from the Belarus border. In any case, European leaders have concluded that Russia and its allies are conducting a coordinated campaign to exert pressure on the transatlantic bloc from within. Yet experts affiliated with NATO and the European Union argue that, across every theater of the emerging struggle, NATO’s collective defense—based on Article 5—shows major weaknesses that could encourage rather than deter hostile actions.

Following the major mistakes made during the first large-scale invasion launched in February 2022 on the orders of President Vladimir Putin, one of Russia’s most successful battlefield breakthroughs in the long war has manifested itself in the implementation of the “triple chokehold” strategy. On the other hand, Putin has stated that the objectives of what Moscow calls its “special military operation” will be achieved “unconditionally.” “If they do not want a substantive discussion,” he said, “then Russia will liberate its historical lands on the battlefield.” Putin added that the previous U.S. administration had “deliberately steered the situation toward an armed conflict,” claiming that Washington believed Russia could be quickly weakened or even destroyed. Russian President Vladimir Putin reacted harshly to European leaders, describing them as “little pigs,” and suggested that Russia would achieve its territorial objectives in Ukraine either through diplomacy or by using military force.[33]

The “Good Cop–Bad Cop” Dynamic in Relations with China

By combining infantry and mechanized ground assaults with artillery strikes and first-person–view drone attacks supported by long-range precision-guided glide bombs, the Russian military has managed to erode Ukraine’s already deficient defensive lines and has made significant advances over the past year. However, the nature of such shadowy conflicts has also exposed some of the difficulties in forming an effective and unified front between Europe’s two leading multilateral institutions, NATO and the EU, which share 23 member states. With regard to NATO, some commentators have noted that the bloc’s “primary focus is on the upper end of military operations and, in particular, on collective defense in response to a conventional Russian attack,” whereas “many responses to hybrid warfare lie in civilian domains where the alliance is less well equipped.” NATO members tested Russia throughout the conflict by gradually increasing military assistance to Ukraine—including long-range missile systems, main battle tanks, and even fighter aircraft—but few explicitly threatened to deploy troops without a potential postwar peacekeeping mission. As Russia consolidated its control over Crimea, the fate of the four regions annexed in 2022 and still subject to fighting became a central area of debate in the peace process led by U.S. President Donald Trump.[34]

The United States will not succeed in its competition with China unless it understands the nature of the game and the strengths and weaknesses of its adversary. Since April 2025, Beijing has believed that its dynamics with Washington have been based on a “good cop–bad cop” game; that is, after leaving meetings with Trump or U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent thinking they had secured a good plan, they were then surprised by anti-China actions from other departments (often the Department of Commerce). Now, however, Chinese leaders appear to believe that they are dealing only with the “good cops” of Trump and Bessent.[35]

China will like two parts of this strategy and dislike the rest. Beijing will welcome the clear statement that the United States prefers not to interfere in the internal affairs of other nations and the explicit affirmation of respect for state sovereignty. This could ease China’s fears that the United States seeks to undermine regime stability. This National Security Strategy will simultaneously reassure and unsettle China. The reassurance comes in the form of promises not to interfere in other nations’ internal affairs and to respect national sovereignty—both long-standing refrains for Beijing, Moscow, Tehran, Pyongyang, and others who resent U.S. lectures on democratic reform. The strategy also rightly criticizes the failures of previous China policies. The critique is harsh, but in retrospect largely fair: “President Trump single-handedly reversed more than thirty years of flawed American assumptions about China—that by opening our markets to China, encouraging American businesses to invest in China, and moving our manufacturing to China, we would facilitate China’s entry into the so-called ‘rules-based international order.’ This did not happen.”

Beijing will be far less optimistic about the declaration of a new Monroe Doctrine and the call for China to withdraw from Latin America: “For our security and prosperity, the United States must be predominant in the Western Hemisphere… The terms of our alliances and the provision of any assistance must be conditioned on reducing hostile foreign influence, from control over military facilities, ports, and key infrastructure to the acquisition of strategic assets in the broadest sense.”[36]

tyapının kontrolünden, geniş anlamda stratejik varlıkların satın alınmasına kadar, düşmanca dış etkilerin azaltılmasına bağlı olmalıdır.”[36]

Friedrich Merz’s Warning: “We Must Stand on Our Own Feet”

Berlin, Washington’s largest ally, has acknowledged that the United States and Europe are at a crossroads and that the transatlantic order established after World War II has collapsed. Stating that the era of “Pax Americana,” in which the United States guaranteed Europe’s security, is now over, German Chancellor Merz said, “We must learn to stand on our own feet.” Merz noted that the period known as “Pax Americana (American Peace),” during which the United States ensured Europe’s security, has largely come to an end. These remarks are seen not only as a warning but also as an admission of a fundamental rupture in transatlantic relations.[37]

Merz stated that the U.S. security strategy did not, in essence, surprise him, noting that every American administration to date has revised it in the first year of a new president’s term. He said that the document was almost identical to what U.S. Vice President JD Vance said in his speech at the Munich Security Conference in February, adding: “Some parts are reasonable, some parts are understandable, and some parts are unacceptable from a European perspective. I see no necessity for the Americans now wanting to save democracy in Europe. If there were something that could be saved, we would already have done it on our own.”

Emphasizing that the most important issue is what this document means in terms of security policy, Merz stated: “This confirms my view that we must become much more independent from the United States in terms of security policy in Europe and thus in Germany. This is not a surprise, but it has now once again been confirmed and documented. This is the Americans’ new strategy.”[38]

At the Chancellery, Merz stressed that Europe must do “much more” in terms of security and become more independent from the United States so that it can stand on its own against Russia in the event of a war.[39] German Chancellor Friedrich Merz said that Europe can no longer take a “free ride” on U.S. security and must invest more in its own defense in order to become strategically independent. Merz said that U.S. tolerance of low European defense spending “will not continue” and warned that even a new U.S. administration would not return to old assumptions. “We Europeans must be stronger on our own,” he said.[40]

German Chancellor Friedrich Merz also warned of the danger that the United States could permanently distance itself from its European allies. He cautioned, “Do not rely on a post-Trump era.”[41]

German forces have begun their first permanent overseas deployment since World War II. A heavy combat unit consisting of 4,800 soldiers and 200 civilian personnel has been deployed in Lithuania, on NATO’s eastern flank.[42]

Meanwhile, this strategy—consistent with long-held beliefs advocated by officials in Trump’s second cabinet—does not portray Russia as the main enemy. Instead, it scolds Europeans for viewing the country as an existential threat and claims that Russia’s actions in Ukraine have only increased Europe’s external dependencies. While proposing major concessions to end the war (for example, no NATO enlargement), it appears to demand nothing from Russia in return. In practice, Trump’s negotiating team is primarily focused on a commercial reset with Russia. A ceasefire in Ukraine and America’s support for the far right in Europe are seen as tools to achieve this objective. While Washington criticizes Europeans for their previous energy and industrial ties with Russia, Trump’s negotiating circle seems to be pursuing a commercial reset based on the same assets (Russian gas, Arctic resources, rare earth elements).

The strategy is the product of internal bargaining among competing factions within the administration. The first group, aligned with Vance, advocates withdrawing from Europe and reengaging with Russia; the second, the Marco Rubio camp, has long sought to preserve U.S. global leadership; the third, the Steve Witkoff–Jared Kushner camp, is looking for profitable investment opportunities. Taken together, they appear to have converged around a strategy that advances America’s commercial interests at the expense of Europe’s economy, security, and sovereignty. Europeans are told that their deep economic ties with China and their aggressive stance toward Russia are evidence of strategic confusion and naivety. Meanwhile, America’s initiatives toward China and Russia are presented as proof of savvy deal-making and the “America First” strategy. The challenge now facing Europeans is to disregard these admonitions and determine their own course of action with regard to Russia and China.[43]

How Should the Future Roadmap for the United States and Europe Be Drawn?

While reaffirming the importance of transatlantic ties, it redefines Russia, accelerates expectations of European self-sufficiency, and places Ukraine’s future within a tighter, U.S.-led diplomatic process. Europe has entered a more demanding phase in its relations, one in which its security will depend less on American capacity and more on its own ability to deter, invest, and shape the political conditions of regional stability. This strategy also places Washington at the center of any future diplomatic process with Moscow, and Europe is expected to shape its political and security posture around U.S.-led negotiations. This narrows Europe’s strategic role at a moment when the war in Ukraine demands expansion rather than contraction. For allies on the front lines, diplomacy cannot be separated from leverage, and leverage cannot be generated without credible deterrence based on European capabilities.

In essence, if there is a common thread in the Trump administration’s new vision, it is that the Trump team views the world through a purely commercial lens and expects others to do the same. In doing so, it largely underestimates the power of ideology as a strategic driving force that can supersede profit. As a result, the White House is likely to be challenged by forces that do not conform to its preferred worldview: China’s pursuit of dominance in Asia, Russia’s persistent imperialism, and Iran’s revolutionary revisionist interpretation of Islam.

The foreign policies of NATO and European countries have never been fully aligned, even during the Cold War, when the challenge posed by the Soviet Union provided a strong rationale for strategic convergence. Compared to Donald Trump’s first National Security Strategy (2017), the new strategy pushes similar “America First” ideas to an extreme. The 2017 National Security Strategy already emphasized great-power competition and demanded greater burden-sharing, yet it still spoke of a free and open order. Today’s National Security Strategy largely abandons great-power competition as a guiding principle. According to some interpretations, the 2025 National Security Strategy removes the “north star” of China–Russia competition and instead treats the economy as the “ultimate issue.” In effect, Europe’s importance is measured not by shared history or values, but by how well it serves U.S. economic and security interests.[44]

Ultimately, in our view, a stronger Europe is a prerequisite for a resilient transatlantic partnership, given that 2026 and the years beyond will provide a critical test of whether populism is not only a political but also a strategic phenomenon. While the National Security Strategy’s diagnosis of Europe’s economic decline may be correct, it offers no solutions for reinvigorating Europe. Let us be clear: the Trump administration will not lead Europeans toward a transatlantic “age of prosperity” once the war in Ukraine ends.

SOURCE: C4Defence

References

[1] https://www.dw.com/tr/almanya-ba%C5%9Fbakan%C4%B1-merz-uyard%C4%B1-pax-americana-bitmi%C5%9Ftir/a-75150031

[2] https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2025/12/13/trump-europe-embassy-parties-gloom-00689149

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/dec/12/donald-trump-regime-change-europe-us-european-far-right-keir-starmer

[4] https://www.csis.org/analysis/nss-could-destroy-nato-alliance

[5] https://thesecretariat.in/article/trump-s-national-security-strategy-seeks-to-recalibrate-russia-ties-it-may-work-in-india-s-favour

[6] https://www.cfr.org/article/reflections-trumps-national-security-strategy

[7] https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/what-trumps-national-security-strategy-gets-right

[8] https://ecipe.org/publications/nato-after-the-2025-summit/

[9] https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/12/16/nato-collective-security-alliances-nato-life-support/

[10] https://behorizon.org/europes-role-in-the-2025-u-s-security-strategy/

[11] https://www.oiip.ac.at/publikation/nato-in-2025-and-beyond-success-and-peril-go-hand-in-hand/

[12] https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/trump-nss-us-europe-far-right/

[13] https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2025-12-11/debates/4281DC21-390D-44E2-8EA6-EE827414E718/USNationalSecurityStrategy

[14] National Security Strategy of the United States of America, November 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/2025-National-Security-Strategy.pdf

[15] https://www.forbes.com/sites/ilanberman/2025/12/08/what-trumps-new-national-security-strategy-signifies/

[16] https://ecfr.eu/article/reading-trumps-national-security-strategy-europe-through-a-distorted-lens/

[17] https://www.iss.europa.eu/publications/chaillot-papers/low-trust

[18] https://www.stimson.org/2025/experts-react-trump-administrations-national-security-strategy/

[19] https://behorizon.org/europes-role-in-the-2025-u-s-security-strategy/

[20] https://cepa.org/article/europe-after-the-us-decoupling-change-or-be-damned/

[21] https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/dispatches/how-europe-can-strengthen-its-own-defenses-and-rebalance-transatlantic-relations/

[22] https://www.csis.org/analysis/national-security-strategy-good-not-so-great-and-alarm-bells

[23] https://cepa.org/article/plus-minus-americas-national-security-strategy-in-10-points/

[24] https://www.chathamhouse.org/2025/12/trumps-new-national-security-strategy-cut-deals-hammer-europe-and-tread-gently-around

[25] https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/how-much-abuse-can-americas-allies-take

[26] https://icds.ee/en/what-the-new-us-national-security-strategy-really-signals-for-europe/

[27] https://www.npr.org/2025/12/08/nx-s1-5636645/expert-weighs-in-on-how-u-s-relations-with-europe-are-changing

[28] https://www.politico.eu/article/the-trump-effect-how-one-mans-politics-rewired-europe/

[29] https://ecfr.eu/article/why-trumps-national-security-strategy-is-a-geoeconomic-trap-for-europe/

[30] https://www.nytimes.com/2025/12/16/world/europe/ukraine-security-guarantees-talks.html

[31] https://behorizon.org/europes-role-in-the-2025-u-s-security-strategy/

[32] https://icds.ee/en/what-the-new-us-national-security-strategy-really-signals-for-europe/

[33] https://www.theguardian.com/world/live/2025/dec/17/ukraine-russia-war-eu-european-council-frozen-assets-zelenskyy-europe-live-news

[34] https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/a-new-kind-of-war-has-come-for-nato-and-russia-has-the-upper-hand/ar-AA1SvVOy?uxmode=ruby&ocid=edgdhpruby&pc=U531&cvid=694391030676461e9e0250cf29d7f099&ei=15

[35] https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/dispatches/beijing-both-china-and-the-us-think-they-have-the-advantage/

[36] https://www.csis.org/analysis/national-security-strategy-good-not-so-great-and-alarm-bells

[37] https://www.yenisafak.com/dunya/abd-duzeni-coktu-almanya-basbakani-merz-itiraf-etti-4778499

[38] https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/dunya/almanya-basbakani-avrupanin-guvenlik-politikasi-acisindan-abdden-daha-bagimsiz-hale-gelmesini-istiyor/3766408

[39] https://www.euronews.com/2025/12/11/europe-needs-to-do-much-more-towards-security-germanys-chancellor-warns

[40] https://www.dw.com/en/germanys-merz-says-europe-must-end-us-defense-free-ride/live-73003399

[41] https://www.dw.com/tr/almanya-ba%C5%9Fbakan%C4%B1-merz-uyard%C4%B1-pax-americana-bitmi%C5%9Ftir/a-75150031

[42] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/may/22/germany-anti-russian-defence-nato-lithuania-friedrich-merz

[43] https://ecfr.eu/article/why-trumps-national-security-strategy-is-a-geoeconomic-trap-for-europe/

[44] https://www.cfr.org/expert-brief/unpacking-trump-twist-national-security-strategy