“There seems to be something wrong with our ships today.”

British Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty,

Commander of the Battlecruiser Fleet,

31 May 1916 [1]

The First World War, also known as the Great War, began in 1914 following the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The murder escalated into a Europe-wide war that lasted until 1918. During the four-year conflict, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire (the Central Powers) fought against Great Britain, France, Russia, Italy, Romania, Canada, Japan, and the United States (the Allied Powers). Thanks to new military technologies and the horrors of trench warfare, the First World War resulted in unprecedented levels of slaughter and destruction. By the time the war ended and the Allied Powers emerged victorious, more than 16 million people—both soldiers and civilians—had been killed.

In the years before the First World War, the supremacy of Britain’s Royal Navy had not been challenged by the fleet of any other country; however, the Imperial German Navy had made significant progress in closing the gap between the two naval powers. Germany’s strength on the high seas was also supported by its deadly U-boat submarine fleet. After the Battle of Dogger Bank in January 1915, in which the British launched a surprise attack on German ships in the North Sea, the German navy chose to avoid a major confrontation with Britain’s powerful Royal Navy for more than a year and instead based much of its naval strategy on its U-boats.

The Battle of Jutland (May 1916), the largest naval clash of the First World War, secured British naval superiority in the North Sea, and Germany made no further attempts to break the Allied naval blockade for the remainder of the war.[2] As is well known, the First World War was largely defined by land battles taking place on the European continent; the number of naval engagements in this war was relatively small, but they were not insignificant. In particular, the confinement of the German Imperial Navy to its North Sea ports as a result of the success of the United Kingdom’s navy was of great importance. Although the naval battles fought in the Atlantic did not have a decisive effect on the overall course of the war, control of the seas was crucial to winning the war.

One of the main elements of the Allied strategy was the naval blockade imposed against Germany. Essentially, this naval blockade aimed to restrict Germany’s access to the food and raw materials required for the war. On the other hand, the element that was key to the war aims of the Central Powers was the submarine warfare conducted against Allied shipping.[3]

At the beginning of 1916, as a result of their successes in 1915, the Central Powers possessed sufficient reserves to undertake further offensives. While the Germans prepared a powerful attack on Verdun, the Austrians made preparations for an offensive in Trentino; the Turks advanced the siege of Kut-el-Amara and prepared defensive positions to repel relief forces. It is a striking coincidence that all three of these offensives progressed in a similar manner, each beginning with dramatic successes and each ending in near failure.[4]

From the perspective of military strategy, the First World War heralded a new era in naval power—the industrial age. The Battle of Jutland (31 May–1 June 1916) was the largest naval battle of the First World War. It was the only battle in which fleets of British and German “dreadnought” battleships actually confronted one another directly.[5]

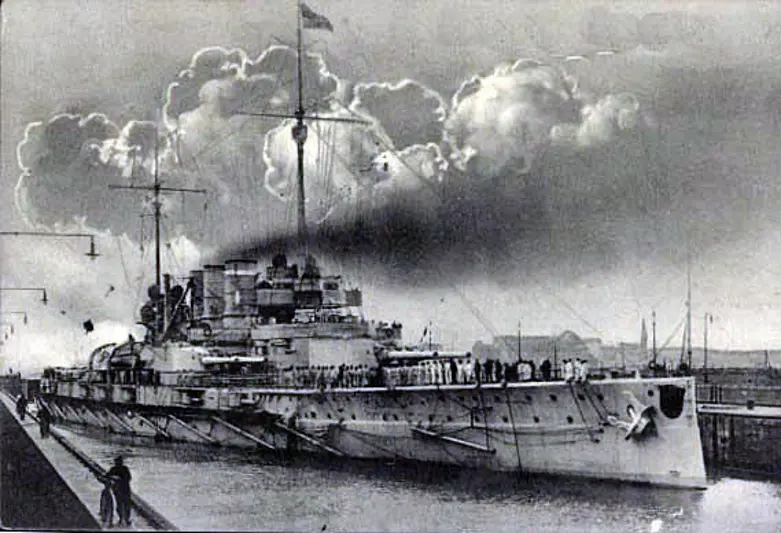

At the gateway to the Atlantic Ocean, where the German Empire’s access was blocked by the Baltic Sea, one of the obstacles to its naval ambitions was geography: German warships first had to sail around Denmark in order to reach the North Sea and the Atlantic. To solve this problem, construction began in 1887 on a new canal that would cut across Denmark from end to end. This canal, formerly known as the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal (now called the Kiel Canal), enabled the German Baltic Fleet to reach the North Sea more quickly from its bases without the burden of sailing around Denmark. Britain regarded the construction of the canal as a direct threat and, in response, the government decided to implement reforms to modernize the British fleet.[6]

The German warship SMS Yorck is sailing in the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal

1916 was a turning point in the First World War. In February, German forces attacked the French at Verdun, and 1 July would mark the opening of the Anglo-French Somme offensive. Yet between these major events, the greatest naval battle of the war—and by some measures the greatest naval battle in history—took place. On the afternoon of 31 May 1916, the full battle fleets of Britain and Germany confronted one another for the first and only time in the North Sea, off the coast of Denmark’s Jutland Peninsula.

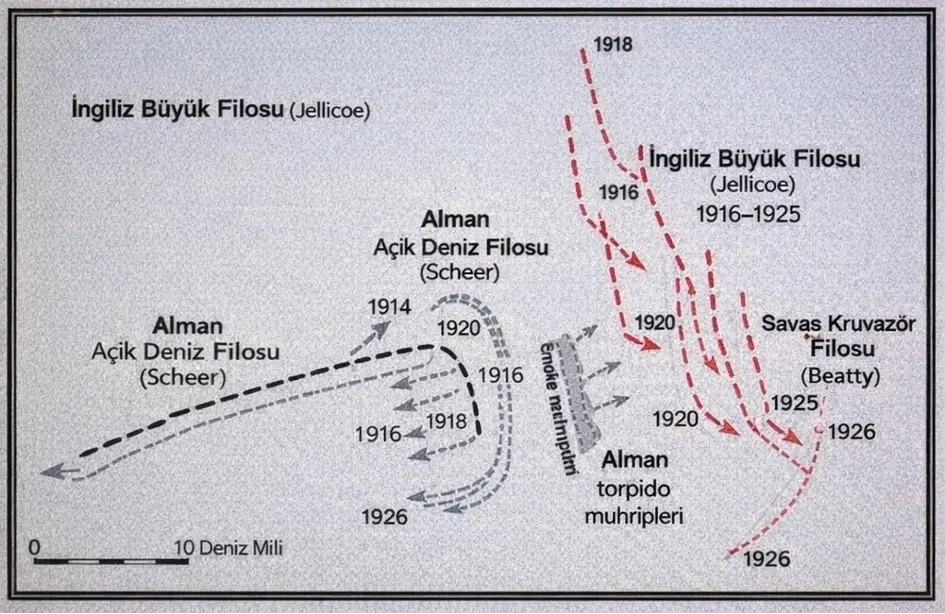

The Battle of Jutland ensured that Britain remained the world’s most dominant naval power, which was Australia’s primary strategic objective throughout the war.[7] The Battle of Jutland (German: Skagerrakschlacht, literally “Battle of the Skagerrak”) was a naval engagement fought during the First World War between the British Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet, commanded by Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, and the German Imperial Navy’s High Seas Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer. The battle unfolded between 31 May and 1 June 1916 off the North Sea coast of Denmark’s Jutland Peninsula, involving extensive maneuvering and three main engagements.

It was the largest naval battle of the war and the only full-scale clash of armored battleships, and its outcome ensured that the Royal Navy prevented the German surface fleet from accessing the North Sea and the Atlantic for the remainder of the war. Germany thereafter avoided all fleet-to-fleet engagements. Jutland was also the last major naval battle in history fought primarily by battleships.[8]

Fought between the British Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet and Imperial Germany’s High Seas Fleet, it was the largest naval battle of the First World War and one of the largest battles in recorded history; approximately 250 warships and tens of thousands of sailors took part. It was also the only fleet battle fought between modern battleships (dreadnoughts) until the final stages of the Second World War.

At the Battle of Jutland in May 1916, the British Grand Fleet enjoyed a numerical superiority over the German High Seas Fleet of 37 to 27 in heavy units, and 113 to 72 in light support vessels.

Although it was not as deadly as the land battles fought by the armies of the belligerent states during the First World War, the Battle of Jutland was the bloodiest naval battle of this global war. The Grand Fleet lost 14 ships and 6,000 sailors; most of these losses were suffered aboard three large battlecruisers that were destroyed with few survivors. The High Seas Fleet, by contrast, lost 2,500 sailors and 11 ships, including one battlecruiser and one pre-dreadnought battleship. Based on the losses inflicted on the larger British fleet, the German Navy declared victory. However, the battle was a strategic success for Britain: the High Seas Fleet remained in the North Sea, and British naval superiority was maintained for the rest of the war.[9]

Lasting for two days beginning on 31 May 1916, the Battle of Jutland was the largest naval battle of the First World War. A total of 151 British warships and 99 German ships faced each other, marking the first and only encounter between the two battle fleets. A wide variety of warship types took part in the battle, each playing a different tactical role. Battleships carried the heaviest guns and the thickest armor. Although they were well protected against gunfire, their size and relatively low speed made them vulnerable to torpedo attacks from smaller vessels.[10]

After realizing that the British would establish a “distant blockade” rather than directly blockading the European coastline in order to avoid mines and submarines, the Imperial Navy began seeking ways to draw parts of the Grand Fleet into battle. Germany’s First Scouting Group, composed of battlecruisers, was used in these efforts together with submarines.[11]

When Admiral Beatty encountered the main German forces, the German Imperial Fleet turned in the opposite direction and executed an escape maneuver. Beatty’s forces pursued, and the lines of ships on both sides continued to exchange fire. The main body of the German fleet drew the engagement northward. The Germans then encountered the main force of British dreadnoughts under the command of Admiral John Jellicoe in a naval situation known as “crossing the T.” The British ships were deployed across the top of the T, with their guns directed toward the German fleet. The ships of the German fleet were aligned bow forward, forming the stem of the T. The most powerful ships of the United Kingdom opened fire. Only the foremost German ships were able to return fire. Within ten minutes, the German fleet came under heavy fire and in a short time took 27 hits. By contrast, during this period the British fleet suffered only two hits. The Germans were forced to turn back and retreat from the battle. Admiral Scheer left supporting ships behind to cover the withdrawal of the German Navy, and these vessels suffered heavy losses. Fighting continued throughout the night; however, most of the German fleet managed to escape back to its main base under the cover of darkness.[12]]

This battle, the only engagement in which large portions of the British and German fleets confronted one another, took place in the North Sea south of Norway. The Battle of Jutland, the last great naval battle in history fought solely by surface ships, involved approximately 250 vessels. In a sense, this great naval battle ended in a draw; however, Germany declared victory because it lost fewer ships and men. In contrast, Britain claimed a strategic victory, as the German High Seas Fleet never again posed a serious threat to British waters throughout the First World War.

At the Battle of Jutland, both sides employed a variety of ship types. Battleships possessed the largest guns and the thickest armor plating. Battlecruisers were as heavily armed as battleships but were faster because they carried less armor plating. Light cruisers were generally used as protective escorts for the slower battleships. Destroyers were the least heavily armed ships and had little or no armor, but they could launch torpedoes and move faster than all other categories of ships; these advantages made them a serious threat to battleships.[13]

Modern understanding of the First World War has focused on the immense human losses of land warfare filled with trenches, artillery, and machine guns; however, the war was won by naval power. In August 1914, Britain, the greatest naval power of the age, took control of the oceans and deprived Germany of global resources. Without imported raw materials and food, Germany could fight for only one or two years before facing starvation and industrial collapse. In order to break the heavy blockade, Imperial Germany’s High Seas Fleet had to defeat the British Grand Fleet, which was based at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands and had closed the North Sea to German ships.

Numerically and materially superior, the British Grand Fleet finally confronted the German Navy nearly two years after the outbreak of the war, on 31 May 1916, in the Battle of Jutland, the greatest naval battle in history. The German Navy sailed north with a plan to encircle and destroy part of the Grand Fleet. The British, forewarned by radio intelligence, steamed south with the intention of trapping the entire High Seas Fleet.[14]

The year 1916 was the year of great battles of materiel—Verdun and the Somme, as well as Jutland—in which the crude industrial power of the Western Allies began to wear Germany down in a way that uninspired military leadership had failed to achieve. Jutland was both the first and the last great clash of battleships, the technological marvels of their age. For both naval powers, the mechanized destruction inflicted upon crews and warships was horrifying. Although the entire engagement lasted only 12 hours, it was a nightmarish experience for thousands. In terms of ships and personnel losses, the German High Seas Fleet emerged with a narrow victory. Yet sometimes even inconclusive battles can be decisive, and in this case the even harsher word “decisive” may be appropriate. Why did the High Seas Fleet never fight again?[15]

This brief military history article carefully analyzes tactical mistakes that can serve as strategic examples for present and future naval warfare, as well as historical cases of responsibility in command decisions; the open-sea battles of large fleets; the maneuverability of submarines and torpedo boats; the economic and military consequences of naval embargoes; mine warfare; deception, avoidance, and concealment; meteorological conditions; aerial reconnaissance intelligence; communication techniques between ships; naval logistics and freedom of navigation; and the fact that violations of the immunity of civilian vessels under international law constitute war crimes.

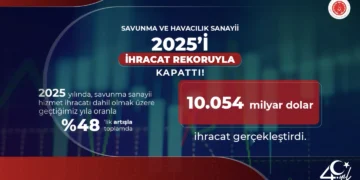

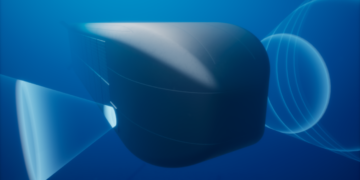

It is assumed that this article, which contains lessons that will affect NATO’s future war strategies as much as it has influenced the Russia–Ukraine War in the Black Sea through beyond-the-horizon ballistic missile attack tactics by submarines and warships, aircraft carriers, satellite warfare, and the dangers and surprise-attack tactics created by unmanned maritime vehicles, should be taken into consideration by the Turkish Armed Forces and maritime trade experts. In this respect, Turkey is closely monitoring the attacks carried out against Turkish merchant vessels in the Black Sea and is, for the time being, reserving the necessary countermeasures.

The second important lesson is that the dangerous alliance initiative launched against Turkey in the Mediterranean by the “Israel–Greece–Greek Cypriot Administration” trio is being watched with concern, as it is seen as an attempt to weaken the Ankara–West axis through provocation. Between the Aegean and the Mediterranean, blockade plans against Turkish seas may prove insufficient against the rising Turkish Naval Power; moreover, in the context of maritime law, the protection of the Turkish merchant fleet and the keeping of our sea lanes open are of great strategic importance for Turkey in the twenty-first century—this constitutes the main idea of the article.

The third and most important message is that, as part of “Hybrid Warfare Tactics,” the media’s negatively destructive effect on the fighting will of military personnel and the civilian population must be taken into account. At present, attack tactics employing Artificial Intelligence (AI) and “fake news” are being used via social media to spread false reports claiming that warships have sunk and that the war has been lost, with the aim of driving the public into chaos and revolt. Indeed, the British press fell into this trap during the naval battles of Jutland, causing social fractures that continue to this day.

Pre-War Political and Military Developments

In a technological arms race, it is generally preferred to build the most advanced and highest-quality weapon systems. Britain faced precisely such a decision at the beginning of the twentieth century. After fifty years of evolution in naval technology, Britain launched HMS Dreadnought in 1906, a revolutionary ship that combined the largest guns, the strongest armor, and a new steam turbine engine in a single battleship. All previous warships were rendered obsolete, and a new naval arms race began.[16]

In 1906, the British initiated what became known as the dreadnought era: HMS Dreadnought was, for its time, the fastest battleship in the world and carried ten massive guns capable of long-range fire. This class of ship became widely known as “dreadnoughts,” leading to a naval arms race between Britain and Germany to develop ever larger and more capable battleships. In 1907, the German Navy responded to Britain by launching its own version of an armored battleship, SMS Nassau. Each year, both countries attempted to produce more battleships than the other, and by 1914 Britain had 22 dreadnoughts, while Germany had 15 of the same type as Nassau. With the outbreak of war, these two massive navies would struggle fiercely for control of the seas.[17]

In 1915, while the Germans launched an offensive on the Eastern Front, Germany simultaneously began attacks on the high seas through submarines operating from bases in Germany, Belgium, Austria, and Turkey. As German Admiral von Tirpitz himself admitted, this offensive was launched somewhat prematurely, as the Germans were not truly ready to implement it in February 1915. Consequently, in the first months of the campaign, the damage inflicted on Allied and neutral shipping was relatively limited. As the number of submarines increased and their crews became more proficient, the number of ships they sank also rose, as reflected in the figures for the third quarter of 1915. However, due to restrictions imposed on submarine commanders by the German government in response to strong protests from neutral countries, the damage inflicted on shipping remained at approximately a constant level during the last two quarters of 1915 and the first two quarters of 1916. These protests reached their peak after the Sussex incident in March 1916, when the Germans pledged to conduct cruiser-style warfare with their submarines. As a result, submarines did not significantly affect the course of the war prior to the Battle of Jutland.[18]

In the late spring of 1916, after months of calm in the North Sea following the naval operation at Dogger Bank, the main fleets of Britain and Germany faced each other for the first time. Paradoxically, it is clear that the avoidance of direct conflict by the navies up to that point was not coincidental. For the Royal Navy, control of the seas was of paramount importance. The entire perspective shaped by centuries of tradition was based on the assumption that as long as the sea lanes remained open for trade, the future of Britain and its empire was secure. With the German main fleet confined to German ports, this condition had been more than satisfied. Only the Germans’ submarines (U-boats) had the capacity to threaten the security of the British merchant fleet, and at this stage of the war, their successes were limited. The British were not averse to engaging their German counterparts. In fact, the British welcomed a confrontation on the open seas, believing that their numerical superiority and firepower would provide a significant advantage in open waters. However, falling into a trap of German submarines and torpedo boats in their home waters was obviously not advisable. In this context, the British thought it best to leave the German High Seas Fleet alone as long as it caused no direct harm.[19]

The Battle of Jutland, which took place from 31 May to 1 June 1916, must be understood in the context of Australia’s strategic reasons for entering the war in 1914, aside from loyalty to the British Empire. They were dependent on the British Navy for security against the rising power of Japan, and if the Allies had been defeated by Germany, this security would have been lost. The Australian Imperial Force (AIF) fought on the Western Front to help prevent this, but if Germany had succeeded in destroying British naval power at sea, avoiding defeat on land would have been in vain. This power was embodied in the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet, stationed in Scotland.

Comprising 28 battleships and 9 cruisers, this fleet was not only the ultimate guarantor of Australia’s security. By merely being there, it prevented any direct attack on Britain and disrupted Germany’s war efforts by blockading North Sea and Baltic ports. Therefore, the integrity of the Grand Fleet was vital for the Allies’ hopes of victory in Europe and for Australia’s protection from Japan. On the other hand, in 1916, with a decisive breakthrough on land becoming increasingly unlikely, Germany’s hopes of winning the war depended on delivering a crushing defeat to the Grand Fleet. Thus, Germany needed to engage in a major naval battle and win it. Conversely, Britain did not need to win a battle; strategically, it was sufficient to keep the Grand Fleet intact and avoid defeat.

This is what Churchill meant after the war when speaking about Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, commander of the Grand Fleet: “The only man who could lose the war in an afternoon was on either side.” He feared that a full-scale clash could result in a catastrophic defeat similar to what Japan inflicted on the Russian Navy at Tsushima decades earlier. However, avoiding battle was not the Royal Navy’s style. Naval traditions compelled them to seek a decisive victory, like Trafalgar, even to demonstrate that they were the successors of Admiral Nelson. And they had reason to be confident. The Grand Fleet vastly outnumbered the German High Seas Fleet’s 16 modern battleships and 5 cruisers.

Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy (Kaiserliche Marine) had existed since Germany unified into a single state under Prussian dominance in 1871, combining numerous kingdoms and principalities. German Emperor Wilhelm II was determined to make Germany a world power, and in 1897 he appointed Rear Admiral (later Grand Admiral) Alfred von Tirpitz as State Secretary of the Imperial Navy Office (Reichsmarineamt). Tirpitz was a strong advocate for the need for a larger navy, and within a year he persuaded the German parliament to pass the first in a series of naval laws providing for the construction of 19 battleships and 50 cruisers. The British responded in kind, and a costly arms race ensued between the two powers, fiercely supported by popular nationalist lobbying on both sides of the North Sea.[20]

Kaiser Wilhelm and his advisers, recognizing the importance of naval power for elevating Germany to a position of global strength, faced a dilemma. Germany could either accept Britain’s naval supremacy and build power within that framework, or challenge Britain’s dominance by preparing a fleet capable of defeating its naval power. Experience initially favored the first option: in the 1880s, Germany had acquired colonies totaling five times the area of its European homeland, largely with Britain’s support. German merchant shipping, the second largest in the world, relied on British ports and the protection of British warships for global trade. German naval officers were trained aboard British-style ships, using British coal, techniques, and equipment; in many ways, British and German naval officers resembled brothers.

Thus, one option was to strengthen relations and potentially cooperate with Britain as allies at sea. However, the appointment of Admiral Tirpitz indicated that the second option had been chosen. In the minds of the German Emperor and millions of Germans, the question arose: why should an island empire automatically grant Germany the right to dominate the seas? At any moment, Britain could blockade German coasts, trap German ships in port, and seize German colonies. Why should the German Empire rely on British tolerance, and what benefit would gifts from other nations confer upon Germany? Geographical conditions also prompted conflict. German merchant vessels leaving ports such as Hamburg or Bremen on the Baltic or North Sea had to sail around the North Sea or northern Scotland to reach the Atlantic or other oceans. To protect these merchant ships, the German fleet needed to be at least as strong as the British Navy. Britain would not allow this, because a fleet powerful enough to protect German commerce on the high seas would also be strong enough to launch attacks against Britain, threatening British supremacy and putting its colonies at risk. Therefore, the German navy’s goal of protecting German commerce on the high seas conflicted with British interests. Diplomats in Britain considered it highly unlikely that Germany could achieve maritime security without threatening the Royal Navy’s dominance.[21]

Germany’s main naval fleet, the German High Seas Fleet, was stationed at Wilhelmshaven. The Imperial German Navy was the world’s second-largest navy after the Royal Navy, and in 1916 the High Seas Fleet consisted of approximately 100 ships, 22 of which were battleships (16 of them dreadnoughts). From January 1916 onward, overall command was held by Admiral Reinhard Scheer (1863–1928), whose flagship was the battleship Friedrich der Grosse. Despite Emperor Wilhelm’s desire to keep the fleet intact, Scheer was determined to lure the British Grand Fleet out of its secure home base into open waters, believing he could deliver a blow that would disrupt the enemy’s distant but highly effective blockade of Germany. The greatest risk in this plan was that the British fleet was stronger than the two German fleets combined due to its numerical superiority in battleships.[22]

In the spring of 1916, following intense international pressure, Germany announced an end to its unrestricted submarine attacks on transatlantic merchant shipping. In response, Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer called all submarines into action. As is well known, the Unrestricted Submarine Warfare was implemented by Germany in two separate periods during the First World War. It was a strategy aimed at disrupting maritime trade by targeting commercial and passenger vessels without warning. The first period began on 4 February 1915 but was curtailed by late 1915 due to international backlash and concerns over U.S. entry into the war. Germany resumed this strategy on 1 February 1917.

Essentially, three days after the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare in 1917, the United States severed diplomatic relations with Germany. Earlier, on 7 May 1915, the German submarine U-20 torpedoed the Cunard passenger ship Lusitania off the coast of Ireland. Approximately 1,200 men, women, and children were killed, including 128 Americans. The Allies and the Americans viewed the sinking as indiscriminate warfare, while the Germans argued that the Lusitania was carrying war materials and was therefore a legitimate target.

German High Seas Fleet at the Port of Kiel

Facing the possibility of the United States entering the war over the incident, Germany backed down and ordered its U-boat fleet to spare passenger ships. However, the order was temporary. Germany began constructing new and larger U-boats to break the British blockade, which threatened to starve Germany out of the war. In 1914, Germany had only 20 U-boats; by 1917, the fleet had grown to 140 vessels, and German U-boats had sunk about 30% of the world’s merchant shipping.

At the dawn of 1917, the German high command pushed to resume unrestricted submarine warfare, removing from duty those opposed to the policy, which aimed to sink more than 600,000 tons of shipping per month. Germany was already facing food shortages and had implemented unpopular conscription in its armed forces and war industries. German planners hoped that by breaking the blockade at key British supply ports, they could force Britain out of the war within a year. U-boats resumed unrestricted attacks on all ships in the Atlantic, including civilian passenger vessels. Though concerned that the U.S. might intervene, German military leaders calculated that they could defeat the Allies before the United States could mobilize and send troops to Europe. While President Wilson officially severed diplomatic relations with Germany in February 1917 when unrestricted submarine warfare resumed, he remained uncertain about the extent of public support and initially refused to request a declaration of war from Congress, arguing that Germany had not yet committed “actual overt acts” requiring a military response.[23]

Having failed to gain control of the seas from the British at the Battle of Jutland in 1916, Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare on 1 February 1917. This, along with the Zimmermann Telegram, led the United States to enter the war on 6 April. The new U-boat blockade was nearly successful, sinking over 500 merchant ships between February and April 1917, with an average of 13 ships sunk per day in the second half of April.[24]

By early 1917, Germany’s attacks on American ships made the policy untenable, yet President Wilson, campaigning on a platform of peace, hesitated to join the conflict. The final push came when Britain shared the intercepted Zimmermann Telegram with the United States, revealing Germany’s promise to help Mexico reclaim American territory if it entered the war. On 2 April 1917, President Woodrow Wilson delivered a special address to a joint session of Congress, requesting a declaration of war against Germany. Both the Senate and the House of Representatives voted overwhelmingly in favor, and on 6 April, President Wilson signed the formal war declaration, stating that “a state of war exists between the Imperial German Government and the people and Government of the United States of America.”[25]

With the submarines left idle, Scheer, as the new commander of the High Seas Fleet under Emperor Wilhelm II, had to develop another plan for their use. He aimed to lure part of the Grand Fleet out by sending a portion of his fleet to attack a British port. Meanwhile, the submarines would wait at the mouths of Forth Bay, Moray Firth, Scapa Flow, and other enemy naval bases to strike as British ships rushed out to protect the mainland. German surface ships would then draw the enemy fleet even farther from the British mainland, bringing them within the waiting range of the German fleet. If executed correctly, Scheer’s daring plan could have broken the British North Sea blockade that was gradually strangling Germany.[26]

The Germans were also aware of the inherent dangers of engaging the British in battle. They protected the Grand Fleet and had no intention of putting their ships at risk unnecessarily. Instead, their policy was to keep the High Seas Fleet in reserve and allow the submarines to undertake the secret mission of gradually wearing down the Grand Fleet, reducing it to a size that the Germans could hope to engage with some chance of success. Ultimately, the submarines failed in this task, and the policy was adjusted to consider the possibility of attacking the Grand Fleet in isolated segments. By April 1914, a serious shadow had fallen over Anglo-German relations. The German state, concerned about “encirclement,” was increasingly worried that, especially from 1908 onward, Britain would convert its existing pacts with France and Russia into a full-fledged military alliance.[27]

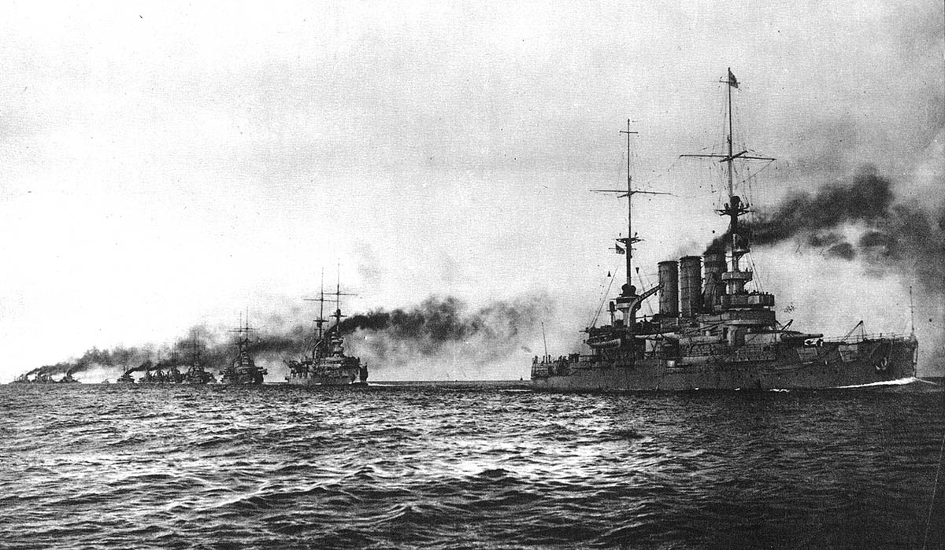

German High Seas Fleet

In mid-January 1916, Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the High Seas Fleet, replacing the cautious Admiral Hugo von Pohl. Scheer believed that a more aggressive war policy could be effective and soon devised a plan in line with this belief. On 25 April, the bombardment of Lowestoft and Great Yarmouth in England by German cruisers was intended to draw part of the British fleet southward into a position where it could be attacked by the High Seas Fleet. The plan worked: Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet, sent the 5th Battle Squadron south from the main British base at Scapa Flow in Scotland to reinforce the Vice Admiral’s command. Sir David Beatty’s 1st and 2nd Battlecruiser Squadrons were at Rosyth. The fleet that Scheer now aimed to intercept and destroy was this reinforced force, before the remainder of the Grand Fleet could steam south from Scapa to rescue it. The German plan was simple.

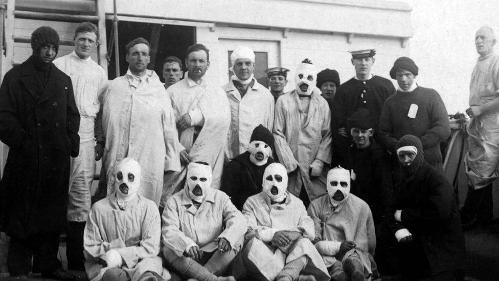

Before the battle, soldiers and the Royal Navy: wounded troops boarding HMS Plassy from HMS Tiger.[28]

Vice Admiral Franz von Hipper was to command a scouting group consisting of the battlecruisers Lützow, Derfflinger, Seydlitz, Moltke, and Von der Tann, accompanied by four light cruisers. Hipper’s force would advance north from Wilhelmshaven toward a point off the Norwegian coast. This force was to be shadowed by battle fleets at intervals of approximately 50 miles. It was hoped that the presence of the scouting unit so far from its base would draw the southern section of the Grand Fleet into pursuit. The main German fleet under Scheer would then close the distance and destroy the British. At 15:40 on 30 May 1916, all units of the High Seas Fleet received the execution signal to implement this plan.[29]

The plan was sound, but numerous delays occurred. Damage previously sustained by the 23,000-ton battlecruiser Seydlitz, armed with ten 11-inch guns, postponed the start of the operation. Submarine commander Captain Hermann Bauer recommended that the U-boats be sent to sea as soon as possible for reconnaissance. Scheer agreed and deployed the submarines in mid-May.

This proved a tactical mistake, as it removed the submarines from the imminent battle. Further delays meant that Seydlitz was not ready until 29 May. By that time, the submarines were running low on fuel, and Scheer’s ambitious plan needed to be executed quickly, or the window of opportunity would close. On that day, Scheer sent another radio message to his submarines with a change in plans. Instead of attacking a British coastal port, the Germans would search for merchant ships around the Jutland Peninsula off northern Denmark. There was a problem with the message: most of the German submarines did not receive it, but the men in Room 40 did. This was the highly secret British Admiralty room where cryptologists intercepted and decrypted German radio signals. The British knew exactly when the Germans set sail and dispatched the entire Grand Fleet to attack them.[30]

Royal Navy of the United Kingdom

“The causes that could lead to a general war have not been completely eliminated; on the contrary, they frequently remind us of their existence. There is no sign of the slightest reduction in military and naval preparations. On the contrary, it is noticeable that this year European states have directed their expenditures toward armaments at levels surpassing all past expenditures. The world is arming itself more intensely than ever before. All proposals to stop or limit this process have proved ineffective.” — Winston Churchill, 17 March 1914, British House of Commons[31]

The Battle of Jutland formed part of a longer naval arms race between Britain and Germany that stretched back nearly twenty years. By the end of the 19th century, Germany’s rulers had made a conscious strategic choice to challenge Britain as a naval power. They saw the construction of a war fleet as part of a post-British international order strategy, marked by the end of Britain’s naval supremacy and the emergence of a German superstate on the world stage. Both countries had spent heavily on building their war fleets prior to the conflict. In this naval arms race, Britain led Germany in the construction of large surface warships. The outcome of the Battle of Jutland was largely predetermined by Britain’s victory in this prewar naval arms race.[32]

The Royal Navy’s main fleet, the British Grand Fleet, was stationed at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands of Scotland. In 1916, the Grand Fleet consisted of approximately 100 ships, 24 of which were the newer dreadnought-class battleships. Overall command was held by Admiral John Jellicoe (1859–1935), a popular leader who was known for his excessive caution and reluctance to delegate responsibilities.

Admiral Sir John Jellicoe’s flagship was the British battleship HMS Iron Duke. As commander of the Grand Fleet, Jellicoe was responsible for the overall command of the British ships during the battle. From the bridge of this ship, he made critical tactical decisions.

Jellicoe’s flagship, HMS Iron Duke, was a battleship.[33] Although both sides possessed the latest naval technologies, the Royal Navy held a clear advantage. The total weight of its 272 heavy guns’ shells was more than twice that of the Germans’ 200 guns. Britain also had more ships in every class and only twelve fewer torpedoes than Germany.[34]

In 1898, Emperor Wilhelm II of the newly formed German Empire decided to challenge England’s centuries-long global naval supremacy by establishing its first fleet. This sparked a naval arms race focused on super battleships known as dreadnoughts. Britain gained the numerical advantage, but new technologies, especially mines and submarines, complicated the equation. When war broke out in 1914, the Royal Navy imposed a blockade on Germany, while German submarines sank Allied shipping on a massive scale. Both sides aimed to starve the other into submission, while the opposing fleets—one at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, the other at Wilhelmshaven in the Jade Bay of the North Sea—waited in a stalemate as deadlocked as the muddy waters off Flanders. Outnumbered, the Imperial High Seas Fleet, under Reinhard Scheer, attempted to level the playing field by raiding eastern coastal towns like Scarborough, hoping to lure Beatty’s fast battlecruisers into a small trap.[35]

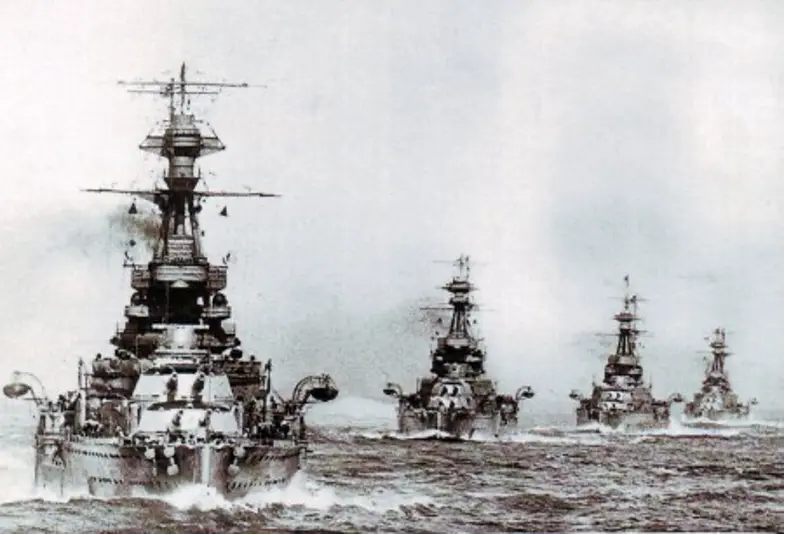

HMS Barham, Valiant, Malaya

For Scheer, this signal was intercepted by British listening stations, and although the details were not fully understood, its wide dissemination made it clear that a large-scale movement of the High Seas Fleet was imminent. Jellicoe was informed, and by 22:30—all before the German scouting group had even departed Jadebusen (Jade Bay)—the entire British Grand Fleet was at sea; Jellicoe’s force set out to rendezvous with Beatty’s force near the entrance to the Skagerrak, directly in the path of the German fleet’s planned route. Hipper put his group to sea at 01:00 on 31 May; they were the vanguard of a fleet of 100 ships, comprising approximately 45,000 officers and sailors. Little did they know, they were about to face 151 ships and around 60,000 men in what would become the largest naval battle in history.[36]

British Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty commanded the Battle Cruiser Fleet that initiated the Battle of Jutland, while Admiral John Jellicoe commanded the Grand Fleet.

The Course of the Battle and Tactical Errors

In March 1916, small-scale raids began. German ships attempting to relieve the blockade struck the coastal towns of Lowestoft and Yarmouth on the nights of 24 and 25 April 1916 in an effort to draw out the Royal Navy. They had also planned a surprise attack along the Danish coast; this plan was discovered by British intelligence, and Admiral John Jellicoe ordered the British fleet to put to sea on 31 May 1916. The High Seas Fleet set out, advancing along the western coast of Denmark. To entice the British to leave Scapa Flow, Scheer used a scouting force under Admiral Franz von Hipper (1863–1932) as bait. This unit consisted of 40 ships, including five battlecruisers and five light cruisers. The German battlecruisers bombarded several British towns with minimal damage inflicted or received. The British, in turn, bombed selected targets in Germany with even less effect.

At the end of May, Scheer sent his fleet to sea with Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper’s battlecruisers leading the reconnaissance. Fourteen submarines were operating off the British bases, and Scheer’s strategy was to attack British ships off Norway, hoping the British would respond with a major force. The plan was set in motion when the British intercepted a coded wireless signal that they believed indicated the German advance. On the evening of 30 May, the British Grand Fleet put to sea from Scapa Flow, Invergordon, and Rosyth. The ships avoided Scheer’s submarines and mines without difficulty, and the Battlecruiser Fleet under Rear Admiral Sir David Beatty moved southeast in search of the Germans.

The German plan aimed to draw out a smaller portion of the British fleet and then destroy it with the full strength of the German navy. However, before the battle, the British had intercepted German communications and learned of the plan.

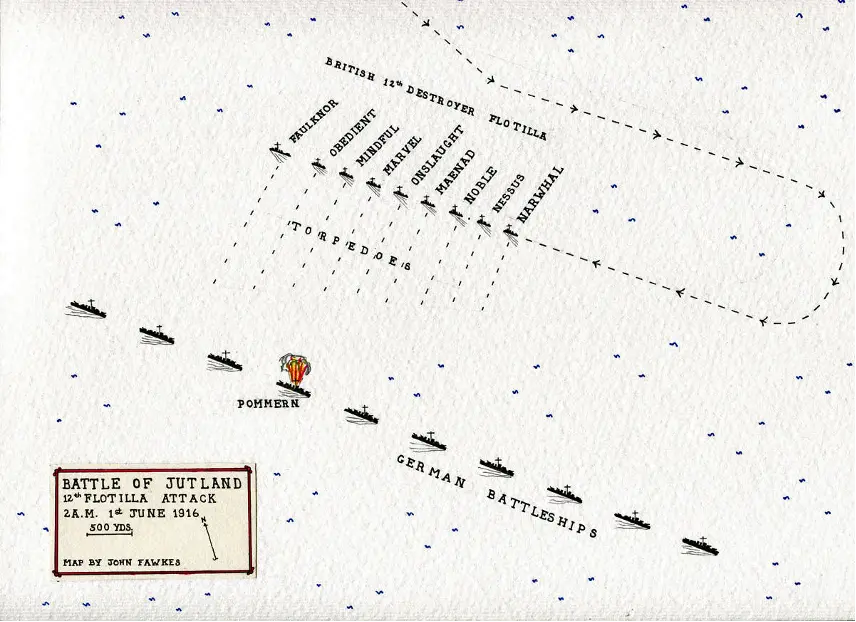

A diagram showing the attack by the British 12th Destroyer Flotilla on the German battle line at dawn on 1 June 1916 during the Battle of Jutland. In the attack, the German pre-dreadnought SMS Pommern was sunk with all hands. The order of the German battleships is uncertain because the ships had to leave the line during the night to avoid torpedoes and later rejoined at gaps in the formation.

Instead, the entire British fleet put to sea to engage the Germans. The battle involved 250 ships and approximately 100,000 sailors. Initially, the German navy gained the upper hand, managing to separate a portion of the British fleet and sink several ships. However, the course of the battle later shifted in favor of the British. Realizing they did not have superiority in firepower and faced the risk of losing the safety of their own ports, the German navy withdrew from the battle.[39]

The German High Seas Fleet at the Battle of Jutland.

Just behind this reconnaissance unit was the rest of the fleet. The British Admiralty’s intelligence service, by intercepting and decoding the unusually high volume of enemy wireless communications throughout May, had easily uncovered preparations for such a large-scale movement of enemy ships. The Grand Fleet was ordered to depart Scapa Flow in the early hours of the evening of 30 May, and by 22:00, the British ships had left the harbor. The first German ships of the High Seas Fleet only set out from port in the early hours of 31 May and proceeded along the western coast of Denmark. To lure the British out of Scapa Flow, Scheer used a reconnaissance unit under Admiral Franz von Hipper (1863–1932) as bait. This unit consisted of 40 ships, including five battlecruisers and five light cruisers. Just behind this reconnaissance unit was the rest of the fleet. The British Admiralty’s intelligence service, by intercepting and decoding the unusually high volume of enemy wireless communications throughout May, had easily uncovered preparations for such a large-scale movement of enemy ships. The Grand Fleet was ordered to depart Scapa Flow in the early hours of the evening of 30 May, and by 22:00, the British ships had left the harbor. The first German ships of the High Seas Fleet only set out from port in the early hours of 31 May and proceeded along the western coast of Denmark.

In addition to losing his element of surprise, Scheer faced two other setbacks: the poor weather, which prevented Zeppelin airships from launching from Germany and serving as ship spotters, and a group of submarines waiting off the coast of Scotland, which could not intercept and engage the British ships. The High Seas Fleet set out and proceeded along the western coast of Denmark. To lure the British out of Scapa Flow, Scheer used a reconnaissance unit under Admiral Franz von Hipper (1863–1932) as bait. The first contact in the battle occurred at 14:28 when the British reconnaissance cruiser HMS Galatea spotted some of Hipper’s ships.

The German battleship SMS Ostfriesland fought on 31 May 1916 at the Battle of Jutland as part of Vice Admiral Schmidt’s 1st Battle Squadron of the 1st Battle Fleet.

The battle had begun. The Germans fired the first shot. A shell struck the ‘Q’ turret of Beatty’s flagship, HMS Lion, causing a deadly fire. Despite being fatally wounded, Royal Marine Major Francis Harvey gave the order to flood the magazine, saving the Lion. He was later posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. At 16:02, two salvos hit HMS Indefatigable, which exploded due to a magazine detonation. Twenty minutes later, HMS Queen Mary, under German fire, also capsized and exploded.[40] Beatty decided to pursue the enemy as Hipper withdrew south, hoping to lure the British toward the larger and approaching German fleet. The two scouting forces exchanged fire. Thanks to more accurate shooting, Hipper gained the upper hand in the initial clash, sinking two British battlecruisers, Indefatigable and Queen Mary, without losing any of his own ships.

The Battlecruiser Engagement initially began when the Battlecruiser Fleet encountered Admiral Hipper’s First Scouting Group of German battlecruisers in what became known as the ‘Run to the South,’ during which both HMS Indefatigable and Queen Mary were sunk. With the arrival of the main German battle fleet from the southeast, the Battlecruiser Fleet turned back and headed toward Jellicoe approaching from the northwest. During this phase, the Battlecruiser Fleet was protected by the fast battleships of the Fifth Battle Squadron, which had been left behind at the start of the operation. This phase of the Battlecruiser Action is known as the ‘Run to the North.’ At the climax of the northward turn, the opposing light forces clashed, resulting in the sinking of two destroyers (British light ships) and two torpedo boats (German light ships).[41] Admiral Beatty remained undaunted and ordered his ships to close with the enemy. By around 16:00, the British realized they were now facing the entire High Seas Fleet. Beatty gave an urgent order to withdraw in order to reverse the German strategy and draw them toward the main British force approaching from the northwest.[42]

Jellicoe rapidly advanced southward with twenty-four battleships and joined forces with Beatty; together, they attacked the Germans. Between 18:30 and 18:45, the two battle fleets exchanged brief salvos. The Germans blew up a third battlecruiser. The British subjected Scheer’s battleships to superior gunfire intensity, but Scheer skillfully changed course, created a smoke screen, and avoided serious damage, though one of Hipper’s battlecruisers was so badly damaged that it later had to be scuttled. Scheer launched another attack but was forced to withdraw at 19:20. He masked his withdrawal with a destroyer attack, yet Jellicoe prudently distanced his fleet from this assault. The main bodies of the two fleets were now separated.

In the Fleet Action, the British battle fleet’s line caught the German battle fleet unprepared, forcing it to withdraw completely twice before escaping into twilight. The British lost the battlecruiser Invincible, the armored cruiser Defence, and one destroyer, while the Germans lost the light cruiser Wiesbaden and two torpedo boats.[43]

Admiral Beatty (Battlecruiser Command), Rear Admiral Arbuthnot (1st Dreadnought Squadron), Rear Admiral Hood (2nd Dreadnought Squadron), Admiral Jellicoe (Grand Fleet), Admiral Scheer (Battleships), Admiral Hipper (Battlecruisers).

Night Operations

The remainder of the battle was characterized by the sinking of German ships and a series of engagements during the night, usually at extremely close range, between opposing vessels. During these encounters, the German fleet managed to pass behind the British fleet, which was attempting to protect the Danish coasts and keep the German fleet at sea for the following day’s battle. The German fleet successfully escaped, and by morning the British returned to their bases.

During the Night Battle, Germany lost the battleship SMS Pommern, the battlecruiser Lützow, the light cruisers Elbing, Rostock, and Frauenlob, and the torpedo boat V4. The British lost the armored cruiser Black Prince and five destroyers: Tipperary, Sparrowhawk, Ardent, Fortune, and Turbulent. [44]

As darkness fell, Scheer resolutely steered his smaller and slower fleet home. Using an extraordinary combination of accurate gunnery and rapid maneuvers, he successfully broke through the British destroyer flotillas covering Jellicoe’s battleships and reached the safety of his mined home waters in the early hours of the next morning. The battle was over.

The British had lost fourteen ships, including three battlecruisers with a total of 110,000 tons, and more than 6,200 crew members were killed or captured. The Germans lost eleven ships, totaling 62,000 tons, including one battlecruiser and one battleship, with 2,500 crew members killed. The battle did not significantly alter the relative strength of the two fleets, and therefore no side achieved a decisive victory.

The battle is divided into five distinct phases. The first was the battlecruiser clash in which Beatty pursued Scheer’s forces southward. This was followed by Beatty’s northward advance after Hipper’s encounter with the main German fleet, with two objectives: to protect the battlecruisers and to lure the High Seas Fleet within range of Jellicoe. The engagement between the two main battle fleets then occurred in two short, destructive, but essentially inconclusive clashes.

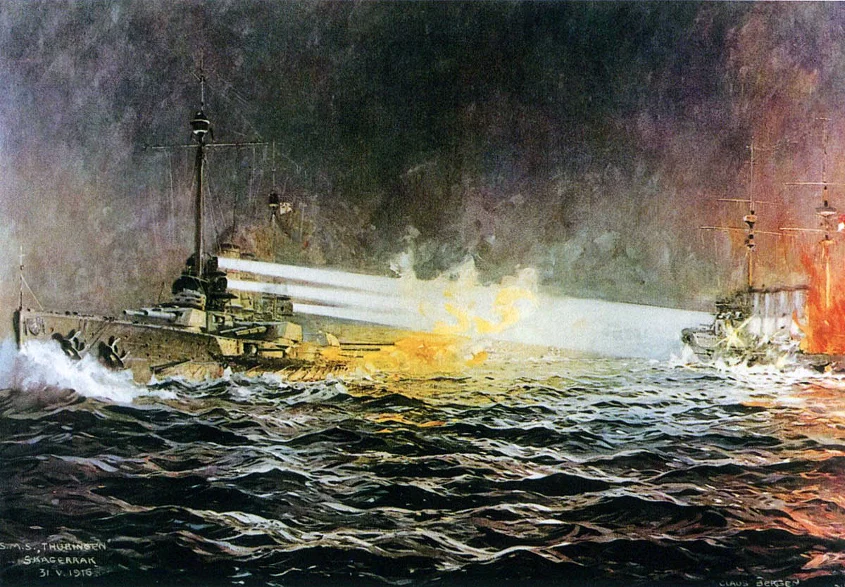

The destruction of the British armored cruiser HMS Black Prince during the night of 31 May 1916, in the Battle of Jutland.

The day on which these great fleets clashed disappointed the high expectations of leaders and peoples on both sides of the North Sea. Although there were dramatic moments during the battle, by the end of the day, neither side had achieved a decisive victory. What the Battle of Jutland demonstrated was the lethality of modern naval warfare: in a single day, the two fleets together sank 25 warships and lost more than 8,500 men. At critical moments in the battle, if the commanders of both the British and German fleets had not acted to avoid the risk of their battleships being destroyed and instead withdrawn from engagement rather than pressing the attack, these losses would have been even greater.

Throughout the course of the battle, the admirals took decisive steps that prevented a clear victory. Instead of a single-day showdown to determine naval supremacy, the fleets returned home to tend their wounds after inflicting tremendous damage on the enemy. This inconclusive outcome did not prevent either government from claiming the prize of victory. The day of battle had passed, yet the struggle to control the shared

Conclusion and Assessment: Who Won the Battle and What Lessons Were Learned?

The British press declared this battle a catastrophic defeat, and the public was plunged into despair. For the British people, who were unaware that a major naval battle had taken place, the Battle of Jutland came as a shock. Within an hour, newspaper sellers in London were shouting in the streets: “Great Naval Disaster! Five British Warships Lost!” Flags were lowered to half-mast, stock exchanges closed, and theaters went dark. Abroad, from New York to Chicago to San Francisco, breakfast headlines read “Britain Defeated at Sea!” and “British Fleet Almost Annihilated!”

However, shortly thereafter, British newspapers began to analyze the events with a more measured perspective. The press asked, “Will the shouting, flag-waving [German] public receive anything more than the copper, rubber, and cotton so desperately needed by their government? Not a penny. Will meat and butter in Berlin become cheaper? Not a penny. There is only one measure, the measure of victory. At the end of the war, who held the battlefield?”

Doctrinally, according to Nick Hewitt, the Battle of Jutland in the North Sea in May 1916 effectively guaranteed that Germany could never win the First World War. [46] The battle, fought amid fog and confusion, immediately became a subject of debate and remains so to this day. Who were the real winners? Who were the heroes or villains? As Jellicoe supporter and former Defense Secretary Admiral Lord West reiterated on Radio 4, was it “the battle that won the war,” or was it a missed opportunity to emulate Nelson at Trafalgar in 1805 by decisively destroying the French and Spanish fleets to end the war more quickly?

The outcomes of the Battle of Jutland have always been controversial. Helmut Pemsel conveys a common perspective: the German fleet, in many respects, proved itself not only equal to but even superior to the Royal Navy (in terms of stability, gunnery, and night combat). Although materially the battle was a German victory, it did not affect the overall strategic situation: a complete victory for the German Navy was impossible. [47]

The German battleship SMS Thüringen attacked HMS Black Prince on the night of 31 May 1916, setting it on fire and sinking it.

The truth is that the Germans claimed they had achieved a great victory at Jutland. Very few observers thought the German fleet had any real chance against the British. Up to that point, naval engagements had gone poorly for the Germans. Great Britain held absolute supremacy over the oceans. However, since the German fleet sank 14 British ships and suffered a total loss of 6,600 men, including 6,097 dead, German newspapers joyfully proclaimed that Trafalgar had been reversed. They were partly justified. The German High Seas Fleet had certainly exacted its toll. Yet the British still maintained a substantial numerical advantage over the Germans and were constructing new ships faster than Germany. Although Queen Mary and Indefatigable were lost, replacements were already under construction. There was no change in the relative positions of the two navies. The German fleet remained cornered in its part of the North Sea, and British ships continued to blockade it. [48]

What can we learn from this battle that took place a century ago? One conclusion is that the outcome of a pre-war arms race is a good indicator of whether a rising rival or a dominant superpower will prevail in a maritime struggle. The harmful consequences of arms races and security dilemmas should not obscure the strategic value of military superiority. If the leading power falls behind in an arms race against a rising rival, it ceases to be the leading power. Any future “Jutland” in aviation, cyber, or maritime domains will occur in a high-risk strategic environment between rising and declining great powers. Two lessons can be drawn from this battle. First, it revealed a severe flaw in the management of British fire control systems (safety procedures were overlooked to maximize firing rate); second, the outcome was not sufficient to undermine British naval dominance over Germany. [49]

The Battle of Jutland, which took place on 31 May and 1 June 1916, was a significant naval engagement in the North Sea during World War I, pitting the British Grand Fleet against the German High Seas Fleet. The battle, initiated by the German command under Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer, aimed to lure the British fleet into a trap and inflict heavy damage using submarines and mines. The British, commanded by Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, sought to confront the Germans in response to intelligence indicating a possible German attack. The battle unfolded in several phases, beginning with clashes between light cruisers and escalating to engagements between battlecruisers, resulting in heavy losses for both sides. Ultimately, although the British Grand Fleet suffered more ship losses, the strategic outcome favored Britain, as its fleet remained largely intact and operational. This encounter did not significantly alter the naval balance, but it left a lasting psychological impact on German forces and prompted a more cautious approach in subsequent naval engagements. The Battle of Jutland is often regarded as a defining moment in early 20th-century naval warfare that influenced the course of naval battles. [50]

The British suffered greater losses than the Germans in both ships and personnel: three battlecruisers, three cruisers, and eight destroyers were sunk, while the Germans lost one battleship, one battlecruiser, four light cruisers, and five torpedo boats. A total of 6,768 British officers and crew were killed or wounded, compared to 3,058 officers and crew in the High Seas Fleet. This was the bloodiest day in British naval history, and the publication of these figures as a victory in the German press gave the impression worldwide that the Royal Navy had suffered a serious defeat. However, the important point was that, despite these losses, the balance of power in European waters had essentially not changed. The British still dominated the North Sea, and the Germans had not inflicted sufficient losses to gain a chance of victory in a new operation against the main British fleets. [51]

A large portion of the casualties on the ships resulted from storing gunpowder close to the turrets to achieve faster firing. Additionally, there was confusion among the highest-ranking officers of both the German and British fleets. Admiral Scheer, commander of the German fleet, did not know that Jellicoe was at sea until the ships appeared on the horizon. Although wireless technology was widely available, it was rarely used because transmitting revealed the sender’s location to the enemy; therefore, the primary means of ship-to-ship communication were flags and searchlights. Signals could not be received in smoke, spray, or low-visibility conditions, so small cruisers were placed among the larger battleships to relay messages. [52]

This unique aerial photograph, taken in 1920 at the Hunstanton Coast Guard Station in Norfolk, shows the temporary signal huts and long antenna used to intercept German wireless transmissions. It was one of the most important listening stations on the east coast and had a direct landline connection to London.

This battle exposed serious deficiencies in the British Battle Cruiser Fleet, the vanguard of the Grand Fleet’s reconnaissance force; weak gunnery and signaling practices, combined with the careless use of high-explosive ammunition, led to the destruction of three battlecruisers. In contrast, the Grand Fleet clearly outgunned the German battle fleet in two brief artillery engagements, forcing German Admiral Reinhard Scheer to perform hazardous emergency maneuvers to withdraw from the battle.

Scheer was adamant about presenting the Battle of Jutland (or Skagerrak, as it is called in German) as a German victory, and indeed, more British ships were sunk than German ones during the conflict. The Royal Navy lost 14 ships: eight destroyers, three battlecruisers, three armored cruisers, and suffered 6,784 casualties. The Imperial German Navy lost 11 ships: five destroyers, four light cruisers, one older battleship, and one battlecruiser, with 3,099 casualties. Considering the surviving ships, the German fleet had sustained the greatest damage.

- Why did Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty, commander of the British Battlecruiser Fleet, engage only a portion of his forces against the German battlecruisers in the opening phase of the battle?

- During the battle, why were three British battlecruisers so catastrophically destroyed after being hit by relatively few enemy shells, while the German counterparts did not suffer the same fate?

- Finally, after the British Grand Fleet successfully positioned itself between the German High Seas Fleet and its main base, how did the Germans manage to escape toward the safety of the Horns Reef passage—a route and destination almost immediately known to British Naval Intelligence?

Can all three of these questions be considered a strategic victory for the Royal Navy? [53] During the Battle of Jutland, British and German operations directly reflected the revolutionary impact of radio communication and intelligence. [54]

The Battle of Jutland demonstrated that Germany’s naval technology was superior to that of Britain. Their ships were stronger, their guns more accurate, and their ammunition more destructive. German shells were often able to penetrate British armor; the reverse was not true. Because the German navy was secondary in national life compared to the German army, which consumed the majority of the state’s wealth, German admirals could not convert technological superiority into a strategic advantage against their British counterparts. However, British admirals were also flawed in their strategic stance, as they were servants of naval technology supported by financial and industrial power that had been in relative and irreversible decline since the 1870s. Between 1914 and 1916, the Grand Fleet and its additional fleet of battlecruisers constituted perhaps the largest example of naval power the world had ever seen in terms of firepower, undoubtedly so. Yet, it was a pyramid of naval power that risked collapse under any new technological development that could threaten its integrity. [55]

Like a strategist and statesman, Churchill analyzed the outcomes of the Battle of Jutland with a realist approach, writing: “Had the German Fleet been decisively defeated, the manpower and resources required by the Admiralty for the Grand Fleet could have been redirected to support the Army.” This development could have enabled the British to gain control of the Baltic Sea and prevented the Russian Revolution..

Kaiser Wilhelm II addresses the officers of the High Seas Fleet after the Battle of Jutland.

The Battle of Jutland was more of a clash than a planned naval engagement. In fact, the German High Seas Fleet, “while pursuing what it assumed was an isolated part of the stronger British Grand Fleet, accidentally ran into that fleet itself.” Facing impossible conditions, the High Seas Fleet skillfully retreated and disappeared into the mists of the North Sea, leaving control of the battlefield in the hands of the Royal Navy. Germany never again risked a fleet engagement and increasingly turned to submarines as a way to continue the naval war.

Although it was seemingly a strategic victory for the Royal Navy, the Battle of Jutland was not a Trafalgar. The German fleet survived defeat, and the price paid by Admiral Beatty’s Battlecruiser Fleet, an isolated part of the British fleet, was tragically high. Of the 249 ships that fought at Jutland, 25 were sunk, and 8,500 men lost their lives. The Royal Navy’s share of these losses amounted to 14 ships and 6,000 dead. More than 5,000 of the British casualties occurred on the five largest lost warships: the battlecruisers HMS Indefatigable, HMS Queen Mary, and HMS Invincible, and the armored cruisers HMS Defence and HMS Black Prince. These ships experienced catastrophic internal explosions, leaving very few survivors.

While the Battle of Jutland did not end the deadlock in the North Sea, it had significant strategic consequences. One outcome of Jutland was that it convinced Germany’s naval and military leaders that the German war fleet had very little chance of seizing control of the seas from Britain. Instead, Germany’s rulers aimed to achieve victory by launching an all-out submarine campaign against the world’s merchant ships supporting British and Allied war efforts. The decision for unrestricted submarine warfare proved fateful and self-defeating, as it led to the United States entering the war against Germany.

Thus, the Battle of Jutland, by pushing Germany’s leaders toward submarine warfare, paved the way for their nation’s ultimate defeat in the Great War and for the rise of the United States as a naval and military great power. [57] More than 8,000 soldiers died, many buried in steel coffins weighing ten to twenty thousand tons. Both Imperial Germany and the United Kingdom immediately proclaimed victory after the clash, but the Battle of Jutland more closely resembled a drawn-out stalemate. In the decades following the battle, high-ranking British officers continued to exchange mutual accusations, and this, combined with the carnage of the continental war, overshadowed the valuable lessons of Jutland. [58]

Although the war in the North Sea progressed in their favor after Jutland, the British were seriously disappointed that the High Seas Fleet did not deliver a second Trafalgar victory in the long-awaited major engagement. The British public and naval circles regarded the lack of a decisive outcome as a significant frustration. Jellicoe and Beatty—or rather, the supporters within both admirals’ staffs—blamed each other for the lost opportunities. After Jellicoe was appointed to the Grand Admiralty at the end of 1916, Beatty was placed in command of the Grand Fleet.

At the same time, in Germany, Kaiser Wilhelm II promoted Scheer to full admiral and honored him with the country’s highest military award, the Iron Cross (Pour le Mérite). The German officer corps, which had previously shown a continually divided structure due to internal rivalries, rallied around Scheer, producing various excuses for the tactical mistakes at Jutland. After Scheer handed over command of the High Seas Fleet to Hipper in August 1918, he spent the final months of the war as President of the Naval Command Staff. [59]

Following Winston Churchill, who had fallen out of favor after the Gallipoli Campaign, Arthur Balfour—later famous for the Balfour Declaration—became First Lord of the Admiralty and later commented in London: “It is not the custom of victors to flee.” [60]

Source: C4Defence

References

[1] https://amuedge.com/maritime-risk-and-safety-battle-of-jutland-exposed-flaws-in-british-naval-procedures/

[2] https://www.history.com/articles/world-war-i-history

[3] Tuğba Eray Biber: ‘’I. Dünya Savaşı Tarihi’’, Yeditepe, 2024, s. 123.

[4] https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1921/september/results-and-effects-battle-jutland

[5] https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/what-was-the-battle-of-jutland

[6] https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/zw4c8p3#zkrg9ty

[7] https://historyguild.org/losing-the-war-in-an-afternoon-jutland-1916/?srsltid=AfmBOorfCMX9lOAd_Zu8wbd0_wf5zyWmPaVCZbuQJSLhd6zR30J3VaLv.

[8] Michael Epkenhans, Jörg Hillmann, Frank Nägler: ‘’ Jutland: World War I’s Greatest Naval Battle’’, Editor: Roger Cirillo, Foreign Military Studies, 2015.

[9] https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/b/battle-jutland-war-game.html

[10] https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/a-guide-to-british-ships-at-the-battle-of-jutland

[11] https://www.hudson.org/national-security-defense/a-century-after-the-castles-of-steel-lessons-from-the-battle-of-jutland

[12] Tuğba Eray Biber: ‘’I. Dünya Savaşı Tarihi’’, Yeditepe, 2024, s. 123.

[13] https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2853/battle-of-jutland/

[14] https://theconversation.com/jutland-why-world-war-is-only-sea-battle-was-so-crucial-to-britains-victory-59415

[15] https://www.historynet.com/jutland/

[16] https://theconversation.com/maths-swayed-the-battle-of-jutland-and-helped-britain-keep-control-of-the-seas-59760

[17] https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/zw4c8p3#zq78xg8

[18] https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1921/september/results-and-effects-battle-jutland

[19] https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Jutland

[20] https://www.historyextra.com/period/first-world-war/jutland-the-battle-that-won-the-first-world-war/

[21] Robert K. Massie: ‘’Dretnot: İngiltere, Almanya ve Yaklaşan Savaşın Ayak Sesleri’’, Sabah Yayınları, İstanbul 1991, s.7.

[22] https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2853/battle-of-jutland/

[23] https://www.theworldwar.org/learn/about-wwi/unrestricted-u-boat-warfare

[24] https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-u-boat-campaign-that-almost-broke-britain

[25] https://archivesfoundation.org/documents/declaration-war-u-s-enters-world-war/

[26] https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/trafalgar-in-reverse-the-battle-of-jutland/

[27] Robert K. Massie: ‘’Dretnot: İngiltere, Almanya ve Yaklaşan Savaşın Ayak Sesleri’’, Sabah Yayınları, İstanbul 1991, s.680.

[28] https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-hampshire-36211199

[29] https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2853/battle-of-jutland/

[30] https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/trafalgar-in-reverse-the-battle-of-jutland/

[31] Robert K. Massie: ‘’Dretnot: İngiltere, Almanya ve Yaklaşan Savaşın Ayak Sesleri’’, Sabah Yayınları, İstanbul 1991, s.687.

[32] https://www.fpri.org/article/2016/05/great-war-sea-remembering-battle-jutland/

[33] https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2853/battle-of-jutland/

[34] https://winstonchurchill.hillsdale.edu/world-crisis3-jutland/

[35] https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/may/29/the-battle-of-jutland-the-chilcot-shambles-of-its-day

[36] https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Jutland

[37] https://theweek.com/73108/battle-of-jutland-what-happened-and-why-was-it-important

[38] https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/military-history-and-science/battle-jutland

[39] https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/zw4c8p3#zbhpywx

[40] https://thehistorypress.co.uk/article/the-battle-of-jutland-31-may-1916/

[41] https://www.eiva.com/about/eiva-log/jutland-1916-the-archaeology-of-a-naval-battlefield

[42] https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2853/battle-of-jutland/

[43] https://www.eiva.com/about/eiva-log/jutland-1916-the-archaeology-of-a-naval-battlefield

[44] https://www.eiva.com/about/eiva-log/jutland-1916-the-archaeology-of-a-naval-battlefield

[45] https://www.fpri.org/article/2016/05/great-war-sea-remembering-battle-jutland/

[46] https://www.historyextra.com/period/first-world-war/jutland-the-battle-that-won-the-first-world-war/

[47] https://armchairdragoons.com/wws-jutland/

[48] https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/trafalgar-in-reverse-the-battle-of-jutland/

[49] https://dulwichcollege1914-18.co.uk/essay/theres-something-wrong-bloody-ships-today-battle-jutland-may-31st-1916/

[50] https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/military-history-and-science/battle-jutland

[51] https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Jutland.

[52] https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2016-05-25/debates/16052540000002/BattleOfJutlandCentenary

[53] https://wavellroom.com/2019/11/28/reflections-battle-jutland-broad-questions-from-a-narrow-selection-of-the-secondary-literature/

[54] https://usnwc.edu/News-and-Events/News/Re-enacting-the-Battle-of-Jutland-US-Naval-War-College-tackles-lessons-from-a-WWI-sea-battle

[55] https://www.historynet.com/jutland/

[56] https://winstonchurchill.hillsdale.edu/world-crisis3-jutland/

[57] https://www.fpri.org/article/2016/05/great-war-sea-remembering-battle-jutland/

[58] https://www.hudson.org/national-security-defense/a-century-after-the-castles-of-steel-lessons-from-the-battle-of-jutland

[59] Jeremy Black: ‘’ Bütün Zamanların Yetmiş Büyük Savaşı’’ Oğlak Yayınları İstanbul 2006 s.56.

[60] https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/may/29/the-battle-of-jutland-the-chilcot-shambles-of-its-day